INTRODUCTION

Despite its exceptional herpetological richness, the Perth region (Fig. 1) has been experiencing significant losses in herpetofauna for decades, because of rapid urban sprawl and land development, as well as its numerous associated threatening processes such as habitat degradation, fragmentation, and introduced species (Storr et al. 1978*; How et al. 2022). Land development continues to occur and has recently resulted in the destruction of faunally rich bushlands occupied by rare and locally significant species in the north of the Perth region. One species is officially considered lost from the Perth region, the Ringed Brown Snake Pseudonaja modesta (How & Dell 1994), while one of the world’s most endangered reptiles, the Western Swamp Tortoise Pseudemydura umbrina, is now restricted to only two wetlands in the north of the Perth region (as well as a handful of translocated populations beyond the Perth region), despite a historically greater distribution (Kuchling & Burbidge 1996*; How & Dell 2000; Schmölz et al. 2021; Paget et al. 2023).

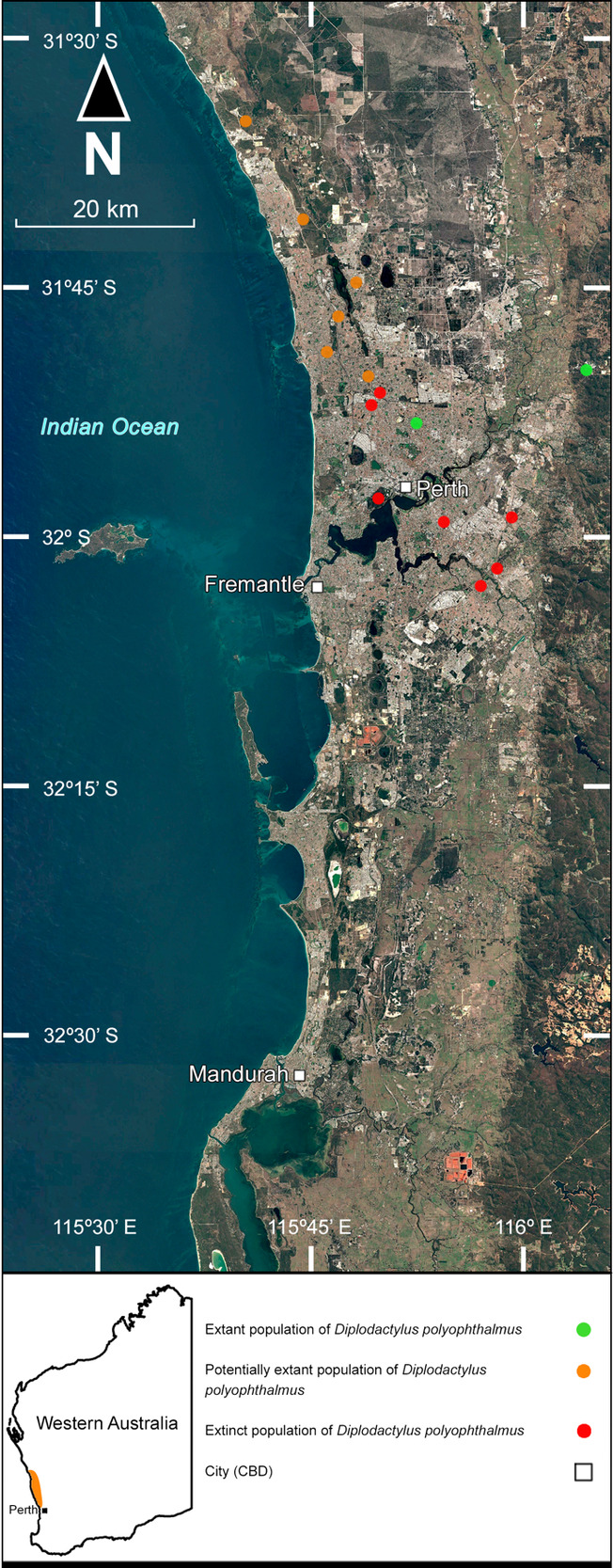

Estimates as far back as 1998 suggested less than 30% of native vegetation remains uncleared on the Swan Coastal Plain in the Perth region (Government of Western Australia 1998*; How & Dell 2000). There has been a further major decrease in the decades since then, particularly with rapid urban development (Western Australian Land Information Authority; https://map-viewer-plus.app.landgate.wa.gov.au/; 20 May 2024). As such, the widespread habitat destruction in recent decades has led to drastic declines in vertebrate species diversity (Storr et al. 1978; How & Dell 2000; Stenhouse 2004; Ramalho et al. 2014). In many small suburban bushland remnants, only the most resilient species may persist, while more sensitive species are quickly lost from such reserves, due to reduced habitat, fewer resources, greater exposure to feral predators, and amplified habitat degradation (How & Dell 2000). In time, even the most resilient species probably will not survive in these small suburban reserves, as resources become exhausted and genetic diversity becomes deleteriously limited. Although biological surveys are always conducted prior to land clearing, they are often too limited in their comprehensiveness and conducted under strict time constraints. This may lead to inaccurate under-representations of local biodiversity assemblages and the potential for threatened species to be undetected (M. Bamford, pers comm., 20 August 2023). Translocation programmes have been proposed as a viable method to mitigate faunal mortalities incurred by land clearing (Thompson & Thompson 2015), but these present several underlying issues pertaining to animal welfare (Menkhorst et al. 2016; Bradley et al. 2023). The deleterious impacts of rapid urban development are most evident in the rarest herpetofauna species, which are known from extremely few, if any, recent records, leading to concerns about their current and future status within the Perth region. This paper reviews six rare species (Fig. 2) characterised by a paucity of information on their current geographical extents within the Perth region, by documenting their historical records, where they may possibly occur undetected and the likelihood of their continued survival. These species have been selected because: (i) their current occurrence in Perth is minimal; (ii) their distributions are ambiguous or data deficient; and (iii) past records indicate a historically greater distribution or abundance in the region. Many such records represent the northernmost or southernmost limits of their distributions (Bush et al. 2010) and as such, populations in Perth are highly significant.

For the purposes of this paper, the Perth region is defined by the administrative boundaries of the local government areas – the City of Wanneroo in the north, the Shires of Mundaring and Serpentine-Jarrahdale, and Cities of Swan, Kalamunda and Armadale to the east, and the City of Mandurah to the south. This encompasses both the Swan Coastal Plain and the Darling Range, which respectively host differing but partially overlapping herpetofaunal assemblages (How & Dell 2000; Bush et al. 2010).

SPECIES

Brachyurophis fasciolatus fasciolatus (Günther 1872)

The Narrow-banded Shovelnose Snake Brachyurophis fasciolatus fasciolatus (Fig. 2a) is a small fossorial elapid snake inhabiting a variety of arid habitats throughout southern Western Australia, such as spinifex deserts, sandy Banksia woodlands and coastal heathlands (Bush et al. 2010; Wilson & Swan 2013). It is known from several historical records throughout the north of the Perth region (OZCAM 2024a; Table 1; Fig. 3). However, recent records are extremely scarce and have only been made in undisturbed expanses of bushland in Yanchep, Ellenbrook and Melaleuca (S. Vinen, pers comm. 17 May 2024; B. Maryan, pers comm. 24 May 2024).

How et al. (2022) recorded only eighteen captures of B. f. fasciolatus in a 35-year herpetofauna monitoring programme at Bold Park, with none being captured after 1999 despite continued annual surveying until 2022. This suggests that the species has since been lost from this reserve (How 2024). Between 1987 and 1999, B. f. fasciolatus was the least frequently recorded fossorial elapid, a trend observed at other reserves throughout the Perth region (Arnold et al. 1991*; Maryan et al. 2002; B. Maryan, pers comm., 24 May 2024). This may reflect a lesser tolerance to human disturbance than other fossorial elapids, although the factors influencing this lessened tolerance remain unclear. Another likely factor is the significant habitat degradation that has occurred at Bold Park, with apparent prolific weed infestations degrading the microhabitats that this fossorial species requires (How & Shine 1999), and few areas of high-quality native vegetation remaining. However, this would not explain the continued persistence of four other fossorial elapid species at Bold Park (How et al. 2022; How 2024).

A single individual was recorded at Maralla Road Nature Reserve in Ellenbrook by Maryan et al. (2002), but subsequent search efforts have failed to locate additional individuals (Irvine 2023). Populations likely persist in the expansive Banksia woodlands west of Tonkin Highway, which was historically continuous with the nature reserve prior to the construction of the highway. Since the initial survey, significant land clearing has occurred within the nature reserve, and the extension of Tonkin Highway has separated the reserve from the vast expanse of bushland towards the west (Western Australian Land Information Authority December 2023*). Other sections of the reserve have been severely degraded by human activities such as illegal dumping of rubbish (Coffey Environments 2016*), likely having a deleterious impact upon B. f. fasciolatus populations there. A deceased individual was found in 2016 in a nearby suburban backyard in Ellenbrook, suggesting the possibility of the species’ persistence in the area (S. Vinen, pers comm. 17 May 2024). Further surveying is required to investigate this.

The capture of a single individual in Melaleuca in 2010 represents what is likely an extant population (B. Maryan, pers comm., 24 May 2024). The Banksia woodlands throughout Melaleuca are expansive and retain high vegetation quality, hence why the species has been able to persist there.

Arnold et al. (1991*) captured a single individual at Whiteman Park in 1986, along with other uncommon and locally significant species such as Ctenotus gemmula Storr, Lucasium alboguttatum (Werner) and Neelaps calonotus (Duméril, Bibron, Duméril). Within the area, expansive habitats remain intact and relatively undisturbed, apart from the recently extended Tonkin Highway separating Whiteman Park from the historically continuous Cullacabardee Bushland. Further surveying is required to ascertain the status of B. f. fasciolatus in this area, as it is possible the species persists to this day.

There have also been two recent observations of B. f. fasciolatus in Yanchep, both in 2022 (J. McGhie, pers. obs.) and in this study (Fig. 2a) confirming that the expansive Banksia woodlands throughout this area supports an extant population.

Snakes appear to have a strong reliance on larger expanses of habitats to survive than lizards, with a positive relationship existing between the richness of snake species and the area of a reserve (How & Dell 1994). This trait increases their susceptibility to habitat fragmentation and B. f. fasciolatus evidently exhibits this trait to a far greater degree than other species.

Ctenotus gemmula Storr 1974

The Jewelled Sandplain Ctenotus Ctenotus gemmula (Fig. 2b) is a semi-fossorial skink patchily distributed throughout southwestern Australia between Cooljarloo and Toolinna, inhabiting sandy Banksia and mallee woodlands, and heathlands (Bush et al. 2010; Kay & Keogh 2012; Wilson & Swan 2013; Bamford et al. 2015*). Populations on the Swan Coastal Plain are listed as Priority Three under State legislation (Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions 2024*). The Priority Three listing is granted for ‘species that are known from several locations’, where there exists ‘significant remaining areas of apparently suitable habitat, much of it not under imminent threat’ (Environmental Protection Authority 2023*, p. 4).

Numerous specimens were collected in the latter half of the twentieth century, indicating the species’ historical abundance within the Perth region, albeit at relatively few locations (Storr 1974; OZCAM 2024b; Table 2; Fig. 4). Forty specimens were collected in Karawara by M. Peterson between 1967 and 1975 (Storr 1974; OZCAM 2024b). However, urban development has resulted in limited habitat remaining today, too little to permit the species’ continued survival (Peterson 2005). Specimens have also been collected from Medina, Jandakot, Whiteman Park, Melaleuca, and Maralla Road Nature Reserve in Ellenbrook (Arnold et al. 1991*; Maryan et al. 2002; OZCAM 2024b). Although sufficient habitat remains at most of these sites, no records exist from the 21st century. Jandakot and Melaleuca have been surveyed intermittently in recent decades but have failed to capture further C. gemmula individuals, despite ample quality habitat remaining (Davidge 1979; Maryan 1993; Bamford Consulting Ecologists 2003*; ENV 2009*; B. Maryan, pers comm. 24 May 2024). Further surveying is required to ascertain the species’ current status at each location but on the basis of recent survey-work, there is a strong likelihood that most populations of C. gemmula in the Perth region have been lost (Maryan et al. 2017).

Recent records of C. gemmula from the Swan Coastal Plain have entirely originated from the Cataby/Cooljarloo area, ca. 150 km north of Perth, where detailed long-term fauna monitoring has been conducted since 1986 and the species has been infrequently recorded (Bamford 1995; Bamford & Calver 2015; Bamford et al. 2015*; Maryan et al. 2017; OZCAM 2024b). As such, it is possible that the population there represents the only remaining one on the Swan Coastal Plain, with all others having been extirpated in recent decades. This may be a matter of serious conservation concern and warrants review by the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA). An elevated conservation ranking above Priority Three may be necessary to recognise the severe decline incurred by Swan Coastal Plain populations of C. gemmula. The nearest extant population is ca. 470 km southeast of Cooljarloo, at the Stirling Range National Park (Kay & Keogh 2012; Fig. 2b), rendering the Cataby/Cooljarloo population an extremely disjunct outlier population.

Delma concinna concinna (Kluge 1974)

The West Coast Javelin Delma Delma concinna concinna (Fig. 2c) is an arboreal pygopodid lizard endemic to coastal regions of Western Australia between Neerabup National Park and Zuytdorp Nature Reserve (Wilson & Swan 2013; OZCAM, 2024c). The species inhabits dense heathlands with complex heath understories and is occasionally highly abundant (Bamford 1998 as Aclys concinna; Bush et al. 2010; Wilson & Swan 2013). The holotype of D. c. concinna was collected in a Sorrento backyard in 1962 (Kluge 1974). Additional specimens have since been collected in primarily coastal localities throughout the northern Perth metropolitan area (Thompson & Thompson 2015; Moore et al. 2015a*; GHD Group Pty Ltd 2018*; OZCAM 2024c; Table 3; Fig. 5). However, many of these records likely represent now-extirpated populations.

The species was captured in a faunal translocation programme at a ca. 14 ha bushland remnant in Alkimos in 2012, which preceded the clearing of that bushland remnant (Thompson & Thompson 2015). All individuals trapped during the programme were subsequently translocated to an adjacent national park (Thompson & Thompson 2015). The presence of the species in such a small bushland remnant demonstrated its ability to persist in small bushland remnants, but how long it can persist before extirpation remains unclear. Therefore, a small number of individuals possibly persist in similarly small bushland fragments throughout the area, which continues to experience ongoing land clearing (Western Australian Land Information Authority; https://map-viewer-plus.app.landgate.wa.gov.au/; 20 May 2024). However, whatever remaining individuals persist would be unlikely to constitute a viable population. This is probably the case for Eglinton, where D. c. concinna was historically recorded, but which is similarly experiencing ongoing land clearing.

The persistence of the species within Neerabup National Park is unsurprising, given that it was historically continuous with Sorrento, where the holotype was collected (Kluge 1974). GHD Group Pty Ltd (2018*) captured a single individual in 2018, confirming that the expansive national park retains an extant population. However, it is unlikely that D. c. concinna continues to persist in the narrow corridor of coastal heath along the Sorrento foreshore, near where the holotype was collected (Kluge 1974).

The species was also recorded at a rehabilitated wetland in Melaleuca in 2011 (Moore et al. 2015a*). Given the size and habitat quality of the vegetation throughout the Melaleuca area, a population likely exists throughout the entire area. However, it is unusual that this was the first capture of D. c. concinna there, as previous surveys have failed to record this species (Huang 2009*; B. Maryan, pers comm. 24 May 2024).

Delma concinna concinna’s scarcity throughout the Perth region is unusual when considering the abundance of the West Coast Keeled Legless Lizard Pletholax gracilis Cope, another pygopodid lizard with which D. c. concinna shares habitat requirements and behavioural similarities – namely an arboreal lifestyle characterised by extraordinarily swift locomotion (Bamford 1998; Bush et al. 2010). In contrast to D. c. concinna, P. gracilis can be relatively abundant even in small suburban bushland remnants, despite its extremely cryptic nature (How & Dell 2000; Bush et al. 2010; Irvine 2023). Despite their contrasting abundances, both species are dependent on high habitat quality and dense heath complexes to facilitate their arboreal lifestyles (Bamford 1998; Bush et al. 2010). While sharing many similarities in their habitat requirements and ecology, P. gracilis utilises both coastal and inland habitats (Kluge 1974; Shea & Peterson 1993; Bush et al. 2010, How et al. 2022), while D. c. concinna appears to be mostly confined to coastal and near-coastal habitats in the Perth region (Bush et al. 2010; GHD Group Pty Ltd 2018*). The factors causing the scarcity of D. c. concinna but not P. gracilis within the Perth region remain to be understood.

Diplodactylus polyophthalmus Günther 1867

The Spotted Sandplain Gecko Diplodactylus polyophthalmus (Fig. 2d) is a small diplodactylid gecko found between Perth and Arrowsmith West (Bush et al. 2010; Wilson & Swan 2013; OZCAM 2024d). The species primarily occupies sandy Banksia and Eucalyptus woodlands but has also been recorded on stony lateritic soils (Bamford 1986; Harris & Bamford 2007*; Doughty & Oliver 2013). It is listed as “Vulnerable” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (Gaikhorst et al. 2017).

Historically merged with the more widespread D. lateroides Doughty and Oliver, D. polyophthalmus is primarily restricted to the Swan Coastal Plain and is one of the rarest geckos in the Perth region (Doughty & Oliver 2013). Throughout the 1980’s and 1990’s, How and Dell (2000) recorded the species in a handful of small suburban bushland remnants north of the Swan River, namely Woodvale, Warwick and Dianella Open Spaces, as well as Kings Park. Additional specimens have also been recorded at several other localities throughout the Perth region (OZCAM 2024d; S. Wilson, pers comm. 26 March 2023; Table 4; Fig. 6), though many of these populations are now likely extirpated (Doughty & Oliver 2013).

Due to the heightened vulnerability of reptiles in small suburban bushland remnants, the current distributions of D. polyophthalmus populations in Perth remains uncertain. The few records in the 21st century have almost entirely come from Dianella Open Space (Irvine 2023; OZCAM 2024d; R. Lloyd, pers comm. 28 April 2024). However, there are concerns for this population’s viability, due to the size of the reserve’s severely limited resources, probably affecting carrying capacity and genetic diversity. Additionally, suburban bushland remnants are extremely susceptible to pollution, feral predators, and habitat degradation (Stenhouse 2004, 2005; Ramalho et al. 2014). A recent site visit identified localised weed infestations that had arisen within a matter of months and no D. polyophthalmus observable in the area, despite extensive searching with one individual being found just three months prior. This reinforces concerns of this population’s fragility and the habitat’s susceptibility to rapid degradation.

The presence of a species within an isolated reserve does not necessarily indicate the persistence of a population, with remaining individuals possibly constituting a functionally extinct population (How & Dell 1994); this is often the case in long-lived species and may indeed be the case for the Dianella Open Space population of D. polyophthalmus. However, the only way to verify this is to undertake long-term monitoring of this population, investigate the population structure and identify the generation length, which is currently unknown.

Dianella Open Space is the smallest reserve where D. polyophthalmus was recorded by How and Dell (2000) and its continued presence at this reserve is anomalous, as it has not been recently detected in other larger bushland remnants in the Perth region. The factors permitting the continued survival of this population are unknown, but the persistence of this species at Dianella Open Space establishes the possibility of D. polyophthalmus persisting at other small suburban reserves throughout the Perth region that retain adequate habitat quality. Many such reserves have not been surveyed systematically, leaving room for further investigation of this matter.

Harris and Bamford (2007*) recorded two forms of D. polyophthalmus at Red Hill (prior to the description and splitting of D. lateroides from D. polyophthalmus in 2013). While a specimen from only one of these forms was collected by them and lodged with the Western Australian Museum (later verified as D. lateroides), it could be inferred that the other form represents D. polyophthalmus. This is the only population on the Darling Range, as well as the only recorded instance of sympatry with D. lateroides, which is restricted to the Darling Range within the Perth region (Doughty & Oliver 2013). Despite the primarily stony habitat being atypical for D. polyophthalmus, Harris and Bamford (2007*) also recorded other reptile species scarcely found on the Darling Range and preferring sandy coastal vegetation, such as Demansia reticulata (Gray) and Pletholax gracilis.

The absence of D. polyophthalmus at Kings Park is unusual, given the reserve’s size and the species’ persistence in the far smaller habitat at Dianella Open Space. Annual surveying has failed to capture the species in three decades (R. Davis, pers comm. 7 December 2023) – the species’ absence may possibly be attributed to the heightened human disturbance and infestations of weeds at Kings Park.

Records from the Perth region, between Perth and Yanchep, have been regarded as one of two disjunct clusters of populations, the other comprising records from between Cataby and Eneabba (Doughty & Oliver 2013; Gaikhorst et al. 2017). However, a record has since been made at Arrowsmith West in 2017, representing the current northernmost limit of the species (OZCAM 2024d). No further specimens have been recorded from Champion Bay or the surrounding area (ca. 110 km north of Arrowsmith West), where the holotype was first collected in the nineteenth century (Günther 1867).

Additionally, the ca. 100 km gap between the northern and southern populations proposed by Doughty and Oliver (2013) neglects to mention specimens captured at Mooliabeenee, located within said gap (Bamford 1986). A single individual was also captured at nearby Boonanarring Nature Reserve in 2012 (Moore et al. 2015b*). However, it does indeed appear that these are the only records in this gap. It is possible that undetected populations occupy the intervening Banksia woodlands within this gap, such as Moore River National Park and Namming Nature Reserve, pending further survey-work in the area.

Another interesting knowledge gap is the habitat preference of D. polyophthalmus. Whilst typically documented as preferring sandy Banksia and Eucalyptus woodlands, the species has also been recorded utilising habitats atop lateritic soils and even appears to be confined to these habitats instead of sandier habitats wherever available (Bamford 1986; Bamford et al. 2015*). As such, the minimal occurrence of D. polyophthalmus on the Darling Range (apart from the Red Hill population), which is characterised by predominantly lateritic soils, is most intriguing. It is possible that the species possesses poor interspecific competitive abilities, with the Darling Range possessing far more gecko species than the Swan Coastal Plain (Bush et al. 2010).

Recent records of D. polyophthalmus originate from only a handful of locations, suggesting that the species may be very patchily distributed and highly vulnerable to local stochastic stressors (Doughty & Oliver 2013; Gaikhorst et al. 2017). Some historical collection sites have not yielded further specimens in recent years, such as Eneabba and Mooliabeenee, warranting additional survey-work in these areas to verify the continued persistence of the species. A review by the DBCA may be warranted, as the species’ overall patchy distribution and drastic declines from the Perth region may be a serious conservation concern (Doughty & Oliver 2013).

Lerista christinae Storr 1979

The Bold-Striped Slider Lerista christinae (Fig. 2e) is a small fossorial skink inhabiting sandy Banksia woodlands and heathlands on the northern Swan Coastal Plain, between Muchea and Mount Adams (Bush et al. 2010; Bamford & Metcalf 2012*; R. Davis, pers comm. 7 December 2023). It is listed as “Vulnerable” by the IUCN (Cowan et al. 2017).

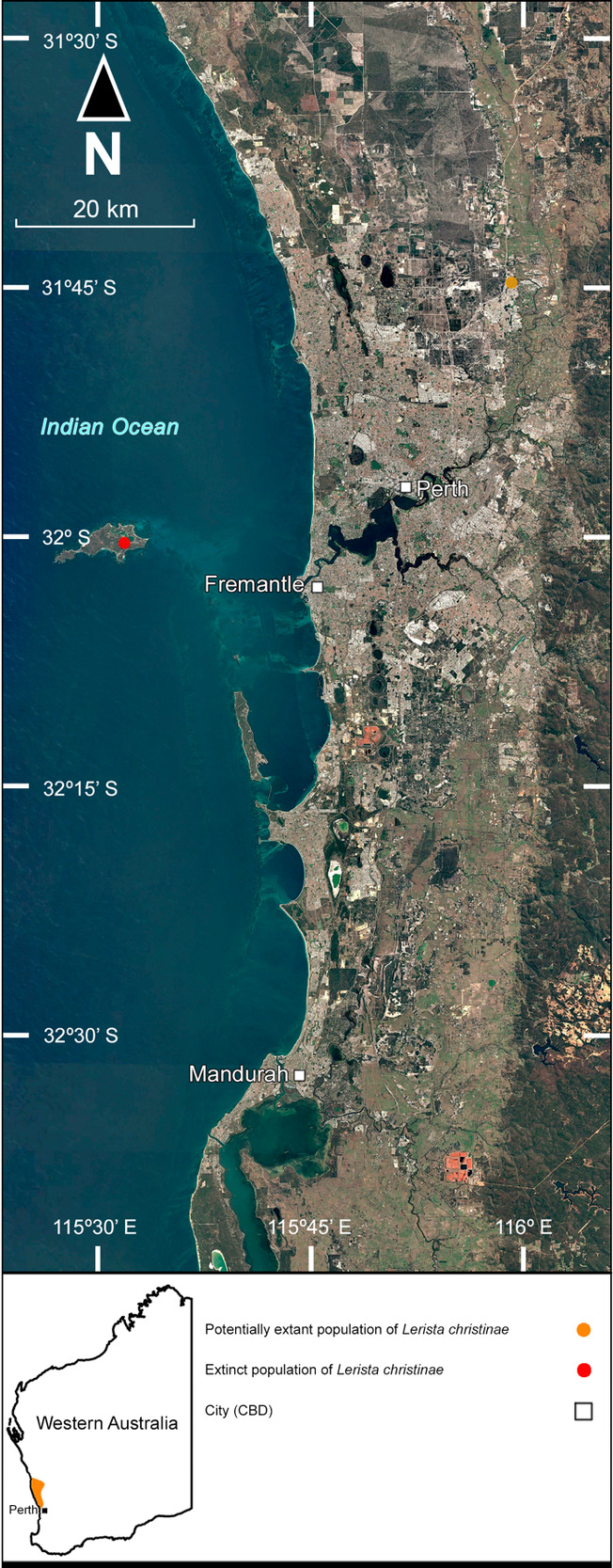

Within the Perth region, Lerista christinae was historically known only from two specimens collected on Rottnest Island in 1970 and 1986 (Smith 1997), before the first mainland specimens were collected at Maralla Road Nature Reserve in Ellenbrook in 1992, representing a significant range extension on the mainland (Maryan et al. 2002; Table 5; Fig. 7). At the time, the species appeared to be relatively abundant at that nature reserve (Maryan et al. 2002). However, subsequent survey efforts failed to locate further individuals there (Irvine 2023), leading to concerns that the species has since been extirpated. Since the initial survey by Maryan et al. (2002), significant land clearing has occurred within the nature reserve, and the extension of Tonkin Highway has separated the reserve from the vast expanse of bushland towards the west (Western Australian Land Information Authority; https://map-viewer-plus.app.landgate.wa.gov.au/; 20 May 2024). Other sections of the reserve have also been severely degraded by human activities (Coffey Environments 2016*), although the effect on L. christinae populations has not been determined. As the species’ range does not extend into inner metropolitan Perth, it is unknown if it can persist in small suburban reserves. While it would stand to reason that L. christinae can indeed survive in small suburban reserves, as can all other locally occurring Lerista spp. (How & Dell 2000; Bush et al. 2010), this would not explain its possible extirpation from Maralla Road Nature Reserve in recent decades. Perhaps L. christinae possesses a lessened tolerance to disturbance than other Lerista spp.

Populations may persist in the expansive Banksia woodlands west of Tonkin Highway and throughout Melaleuca, which was historically continuous with the nature reserve prior to the construction of the highway, however, despite several surveys in this area over the years, the species has not been detected (Huang 2009*; B. Maryan, pers comm. 24 May 2024).

Similarly, the Rottnest Island population has likely been extirpated as well, as no specimens have been recorded since 1986 (Smith 1997), despite extensive surveying on the island (Maryan et al. 2015). Significant human disturbance is a likely factor in the decline of this population, due to increased tourism, reinforcing the possibility that L. christinae possesses a far lower tolerance to human disturbance. However, four other Lerista spp. continue to persist on the island, including the threatened Perth Slider L. lineata Bell (Bush et al. 2010, Maryan et al., 2015).

Based on the most recent records, the range of L. christinae does not appear to reach the Perth region, with none being recently recorded south of Ioppolo Road Nature Reserve near Muchea, just outside of the Perth region (R. Davis, pers comm. 7 December 2023).

Beyond the Perth region, L. christinae occupies sandy kwongan heath and Banksia woodlands north to Mount Adams and is occasionally locally abundant (Bamford 1986; Bamford & Metcalf 2012*). However, recent records of L. christinae originate from only a handful of locations, suggesting that the species may be very patchily distributed and highly vulnerable to local stochastic stressors. A review by the DBCA may be warranted, as the species’ overall patchy distribution and declines from the Perth region may be a serious conservation concern.

Lucasium alboguttatum (Werner 1910)

The White-spotted Ground Gecko Lucasium albogutattum (Fig. 2f) is a small diplodactylid gecko abundant throughout sandy woodlands and coastal heathlands along the Western Australian coast between Melaleuca and Coral Bay (Bush et al. 2010; Wilson & Swan 2013). It is represented by only one extant population in the Perth region, at Melaleuca, with two specimens being recorded in 2009 and 2024 (OZCAM 2024e; He & Kynadi 2024; Table 6; Fig. 8). The Banksia woodlands at Melaleuca are expansive, and retain high vegetation quality, perhaps allowing the species to persist there.

Throughout the latter half of the 20th century, specimens were recorded in Bold Park and City Beach, the last of which was captured in 1995 (How et al. 2022). The absence of further specimens captured during the remainder of their 35-year herpetofauna monitoring programme at Bold Park strongly suggests the species has now been lost from this reserve (How 2024). A possible factor is the significant habitat degradation that has occurred at Bold Park, with apparent prolific weed infestations, and few areas of high-quality native vegetation remaining.

Records of L. alboguttatum at Wireless Hill and Kensington in 1983 and 1990 respectively represent the southernmost records of this species, albeit represented by only a handful of individuals at each reserve (Smith 1985*; Turpin 1990, 1991). However, both populations are likely extirpated, due to the small sizes of the reserves, habitat degradation, and the species’ natural scarcity in smaller reserves (Turpin 1990, 1991; How et al. 2022). Therefore, the losses of these two populations, as well as the Bold Park/City Beach population, represent a significant local range contraction and it is likely that these two populations were first detected when they had already become non-viable and undergoing a decline.

Eleven individuals were trapped in a survey at Whiteman Park in 1986 by Arnold et al. (1991*), indicating its abundance in larger reserves retaining ample habitat quality (though only one was captured there by Drew 1998). Thus, it is possible that the species continues to persist at this reserve, and the historically continuous Cullacabardee Bushland.

DISCUSSION

The contrast between historical and current distributions of these species seems to be a testament to the significant threat posed by land development on herpetofaunal diversity. The deleterious effects of land development probably remain the most pertinent threat towards biodiversity in the Perth region. Due to the rapid progression of land redevelopment in the Perth region (Newman 2014), it is imperative that sufficiently comprehensive studies of faunal diversity and ecology are conducted prior to and in the years after each development. This may aid urban planners in the synthesis of developments that are more conducive to maintaining faunal diversity.

Owing to their cryptic nature, these species are unfortunately denied the same recognition within the public consciousness as more charismatic species, primarily consisting of iconic mammals and birds. A significant impediment to the conservation of these species, among many others, is a paucity of survey effort. Survey-work in the last few decades has significantly extended the geographical limits (or otherwise recorded from unexpected regions) of many reptile species (Turpin 1990, 1991; Smith 1997; Maryan et al. 2002; Algaba 2005; Davis & Bamford 2005; Harris & Bamford 2007*; Davis & Wilcox 2008; Thompson et al. 2008), although some such records were likely made in the midst of the populations’ extirpation, such as the Wireless Hill and Kensington populations of L. alboguttatum. Recently documented discoveries have indicated that populations of cryptic species can persist undetected in un-surveyed or under-surveyed reserves throughout the Perth region, provided they maintain adequate habitat quality. The lack of intensive survey efforts can be attributed to greater environmental impact assessment focus in resource-interest regions, such as the Pilbara and Kimberley (Davis & Wilcox 2008), and areas of heavy development, such as the north of the Perth region. However, some environmental impact assessments have been extremely lacking in comprehensiveness, undertaking basic fauna assessments that only entail a desktop study and a basic reconnaissance survey, referred to as a ‘basic survey’ by the DBCA (Environmental Protection Authority 2020*). In contrast, a ‘basic survey’ entails a comprehensive flora and fauna survey, employing pitfall, funnel and cage trapping to complement the methodologies of a ‘basic survey’ (Environmental Protection Authority 2020*). Employing these methods are more likely to detect these oftentimes cryptic species, with the detection of conservation significant species theoretically (but not always) posing a major barrier to further development.

Furthermore, targeted surveys may be useful in surveying for these cryptic species, with certain methodologies and survey methods drastically favouring certain species. Fossorial species, such as B. f. fasciolatus and L. christinae, can be readily found by raking spoil heaps and leaf litter on warm winter days with a pronged cultivator (Maryan 2002; Bush et al. 2007, 2010; Maryan et al. 2023). Pitfall and funnel traps are industry standard in all biological surveys (Thompson & Thompson 2007) and are often the only reliable survey method to detect particularly cryptic species such as C. gemmula and D. c. concinna. Opportunistic night-time surveys are useful for detecting nocturnal species such as D. polyophthalmus and L. alboguttatum, which are inactive during the day but can be sighted at night as they forage in the open and their reflective eyeshine can be sighted by torchlight (Bush et al. 2007).

The survival of all native fauna in the Perth region seems to have been threatened by urban development, but further research is required to determine the extent of this. Further widespread declines seem inevitable, and this is most likely to affect the rarest species that have undergone severe verifiable declines over the last few decades. Other processes such as climate change and inappropriate prescribed burning regimes may also act as synergistic stressors upon biodiversity (Valentine et al. 2012). The protection of remaining refugia is therefore imperative and contingent on first addressing the knowledge gaps pertaining to these species and their ambiguous presence within the Perth region, with comprehensive biological assessments and survey-work required to accomplish this before further populations are lost.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I thank Dr Mike Bamford, Dr Rob Davis, Jack Eastwood, Greg Harold, Brad Maryan, Danny Melville, Bryce Van Der Heide, Robert Audcent, Ray Lloyd, Steve Wilson, Sonya Vinen, Phillipa Carboon, Dr Calum Irvine and Varkey Kynadi for their assistance, advice and sharing invaluable knowledge and photographs. I am also indebted to Brian Bush (Snakes H & H) and my father Dr Tianhua He for their support and encouragement over the years.

._localities_mentioned_in_the_text_.jpeg)

_*brachyurophis_fasciolatus_fas.jpeg)

._localities_mentioned_in_the_text_.jpeg)

_*brachyurophis_fasciolatus_fas.jpeg)