INTRODUCTION

The tiger snake (Notechis scutatus) population on Carnac Island in southwestern Australia has been the subject of over forty years of scientific research (Abbott 1978; Bonnet et al. 2002; Ladyman and Bradshaw 2003; Aubret and Shine 2009; Burbidge 2024). However, the origin of the Carnac Island population of tiger snakes is difficult to ascertain, and is still under debate. One popular theory posits that 40–100 tiger snakes were translocated to the island during the late 1920s or early 1930s by a snake showman known as Rocky Vane, artificially establishing the population (Ladyman et al. 2020; Burbidge 2024). Research into the history of snakes on Carnac Island has produced a series of accounts that offer insight into this deliberate release, as well as putative evidence that tiger snakes were not present on the island prior to 1929. Here we provide counter-evidence to that presented by Ladyman et al. (2020) and Burbidge (2024), including a summary and analysis of recent genetic data, and suggest that the weight of evidence implies a natural origin for this island population. As much scientific inference may hinge on the origins of this population, we believe that confidence in an anthropogenic origin is potentially misplaced and requires further consideration.

Ladyman et al. (2020) presented several key arguments for population establishment via translocation, including (1) that “Carnac Island is far smaller than any other island along the west coast of Australia that supports a stable population of large elapid snakes”, (2) a lack of historical documentation mentioning the presence of tiger snakes on the island, and (3) evidence that Rocky Vane may have released dozens of captive snakes onto the island. Burbidge (2024) updates the history presented by Ladyman et al. (2020), providing several fascinating insights into relevant events of the early 20th century, and ultimately agreed that “there were no large snakes on Carnac Island prior to 1929”. We discuss these arguments, offer alternative evidence, and investigate the genetic data that is currently available.

TIGER SNAKES ON ISLANDS

Firstly, is Carnac Island unusual in having a stable population of large elapid snakes? Ladyman et al. (2020) used the lack of tiger snakes and other large elapids on southwestern Australian islands—particularly islands < 1000 ha in size compared to > 1500 ha in size—in support of the theory that a naturally occurring population is unlikely. We do not think this is an appropriate way to answer the question. There are hundreds of off-shore islands (> 1 km closest point to mainland) occurring across the distribution of the tiger snake, and the species is known to occur on at least 35 islands around the southern Australian coastline (Atlas of Living Australia, ALA, 2024). Many of these islands have neighbouring islands without tiger snake records, although this may be due to lack of access or adequate survey effort. Importantly, 20 (57%) of the 35 islands are < 1000 ha in area, and many of similar size to Carnac Island, including: (i) Western Australia: Carnac Island; (ii) South Australia: Goat Island, St Francis Island, Franklin Islands East and West, Neptune Islands, Williams Island, Hopkins Island, Grindal Island, Louth Island, Reevesby Island, Blyth Island, Hareby Island, Roxby Island; (iii) Victoria: Clomel Island; and (iv) Tasmania: Christmas Island, New Year Island, Preservation Island, Mt. Chappel Island, Babel Island, and West Sister Island. Seeing as most of these islands known to be occupied by tiger snakes are small in area, we believe this is ample evidence to suggest that tiger snakes have the ability to persist on small islands and island size is not necessarily a key factor for maintaining snake populations. Further, we suspect that many of these populations may not be stable, and, as we discuss below, it is quite possible that population sizes fluctuate substantially through time.

LACK OF HISTORICAL DOCUMENTATION

Next, we consider the lack of historical documentation mentioning tiger snakes prior to the 1930s. Ladyman et al. (2020) considered there to be no documentation of tiger snakes on Carnac Island prior to the 1960s. Burbidge (2024) updated this conclusion with details of the first museum specimen collected by Dr D. L. Serventy in 1934, and discussion of two newspaper articles before 1930 that mention snakes on the island. The first is from 1882, in which rabbit hunters reported that snakes were “plentiful” on the island. The second is from 1914 and is a somewhat less convincing statement about someone’s friend seeing a snake on the island. Burbidge (2024) concludes that these observations must have been mistaken identifications of the King’s skink (Egernia kingii), a situation that we suggest could just as easily be reversed, with members of the general public able to mistake tiger snakes for King’s skinks. Thus, we could similarly question the validity of early King’s skink reports.

Regardless, the absence of historical records of snakes on Carnac Island does at first seem convincing. However, this absence may be due to (1) a true lack of snakes on the island, (2) difficulty in finding snakes on the island, (3) a lack of detailed historical investigation, or (4) a lack of public interest in snakes on the island. Based on surveys and research conducted between 1997 – 2010 years (Bonnet et al. 1999, 2002; Aubret 2015), Carnac Island has a reputation for having a high density (> 20 per ha) of tiger snakes—suggesting that the presence of tiger snakes should be obvious. However, this may not always be the case. The first published survey data on Carnac Island tiger snakes reported the numbers of snakes seen over 70 days of targeted surveying between 1975 – 1977; the highest abundance was in June and November but no snakes were seen on many days (Abbott 1978). Two of the current authors (FA & DCL) have conducted targeted tiger snake surveys on Carnac Island, alongside other experienced snake ecologists. In March 2001, the island was characterised by very dry conditions and dead vegetation with no nesting birds and only two snakes were seen over four days and one night of searching. In February 2019 and January 2020 snakes were targeted over the morning hours for several days each survey; in 2019 ~20 snakes were found, but only ~6 in 2020, with just a single snake being found on one of the mornings. Carnac Island has no permanent free-standing water, and the snake population relies entirely on rainfall, morning dew, and on breeding silver gull (Larus novaehollandiae) colonies for its resources (Aubret et al. 2004; Bonnet et al. 1999). Silver gull population abundance and density has been shown to increase with peripheral human population and urbanisation in Australia since the 1960s, and on Carnac Island specifically (Dunlop and Storr 1981; Smith 1992; Blythman et al. 2023). The high abundance (and other features) of the tiger snake population on Carnac Island observed during surveys from the 1990s onward may be influenced by an increase in silver gull prey availability, which could have fluctuated prior to the expansion of Perth as a city. It is possible that the snake population is subject to something akin to boom-bust cycles—dynamics that are commonly observed in predator populations, especially in response to water availability (Shine and Madsen 1997; Brown et al. 2002; Letnic and Dickman 2006; Pavey and Nano 2013). In this case, small snake population sizes prior to the 1930s would reduce detection rates from visitors to the island.

Further, snakes are often highly cryptic animals, that are notoriously difficult to detect even by experienced observers (Whitaker and Shine 1999; Durso et al. 2011). Diurnal snakes, such as tiger snakes, have basking and activity patterns influenced by season, time of day, and weather conditions (Shine 1979; Butler et al. 2005). Seasons and conditions during Carnac Island historical visits therefore need to be considered alongside observations; for example, we have presented evidence that tiger snakes are less likely to be seen in the late summer months (Abbott 1978). It is well known to snake enthusiasts and researchers that an absence of finding large elapids in seemingly good weather, in locations of typically high abundance, does not mean they are not present. We acknowledge that Carnac Island tiger snakes have blind individuals (Bonnet et al. 1999), and reduced anti-predatory behaviours (Aubret et al. 2011) which likely increase detectability; however, if the snake population does follow a boom-bust cycle, and the island was at times visited during unfavourable conditions, then this would help explain the historical absence of reports of snakes.

TRANSLOCATION TO CARNAC ISLAND

Both Ladyman et al. (2020) and Burbidge (2024) provide evidence for the previously anecdotal story suggesting that the snake showman Rocky Vane released tiger snakes onto Carnac Island. Burbidge (2024) showcases a file note summarising a telephone conversation from a Mr Bydder, who claims to have accompanied Vane in a boat to Carnac Island, after police ordered Vane to get rid of the snakes, and they released 70–100 tiger snakes on the island. Bydder also said Vane planned to release tiger snakes on Garden Island, but this was never substantiated. The evidence, even if anecdotal, is convincing, and perhaps the release did happen. However, this does not prove the absence of a previously existing population. Vane may have simply, either knowingly or unknowingly, been supplementing a naturally occurring snake population. However, questions remain, including why, in an age when snake showmen frequently refreshed their captive snakes with wild-caught snakes, would Vane choose to agist snakes on an island rather than one of the many wetlands around Perth that are rather more accessible? We can only speculate, but perhaps these snakes held sentimental value to him, or they had become accustomed to captivity, being displayed and handled, and were more manageable in shows.

Another consideration is the fate of any tiger snakes released onto Carnac Island. Radio-tracking and monitoring studies around the world show consensus that translocating or releasing captive snakes into novel locations results in irregular, stressed behaviour and high mortality (Cornelis et al. 2021). There is no evidence for where Vane collected his tiger snakes but considering the available genetic data (discussed below) and the abundance of snakes around Perth’s wetlands, we presume these were locally sourced snakes. At present, the tiger snakes of the Swan Coastal Plain are highly associated with wetlands—likely due to cooler microclimates and their preference for frog prey (Aubret et al. 2006). We suspect that translocating wetland-raised tiger snakes to an island with no freshwater or frogs would have resulted in high mortality and likely a very low level of reproduction, if any.

GENETIC DATA

There have been two studies published that have investigated the genetic relationship between Carnac Island tiger snakes and mainland populations, with recent genetic data available online. The first of these, Keogh et al. (2005), demonstrated that the Carnac Island population is not affiliated with populations from the eastern states, and is part of the broader Perth population of tiger snakes. The implication of this is that, if Vane did release snakes onto Carnac Island, he presumably released snakes that were captured in southwestern Australia, and likely from the Perth region. The second study, Lettoof et al. (2021), showed that Carnac Island tiger snakes are moderately differentiated (G″ST ≥ 0.29) from any sampled Perth populations, which appears to be a classic example of vicariance and genetic drift, observed in many island populations of Australian vertebrates (von Takach et al. 2021; Rick et al. 2023). Lettoof et al. (2021) demonstrated that the Carnac Island population was most closely affiliated with populations sampled within proximity of Rockingham, the most biogeographically logical place for a population of natural origin to be related to. And lastly, Lettoof et al. (2021) also demonstrated that the Carnac Island population contained a lot of unique genetic variation (in the form of ‘private alleles’). This unique variation suggests that the population is not derived solely from relocated Perth snakes, but rather that it has been present on the island for a long time, accumulating novel mutations. The only other explanation for this unique diversity is that the population was partially derived from a population outside of the Perth region, which, as we have already established, does not fit particularly well with the findings of Keogh et al. (2005). Given this, we posit that if Vane did release many snakes onto the island, and those snakes did survive, the effect was just to supplement an existing population with additional genetic diversity, perhaps driving the relatively high values of heterozygosity that were observed in Lettoof et al. (2021), which are perhaps atypical for isolated island populations that have experienced genetic drift over recent millennia.

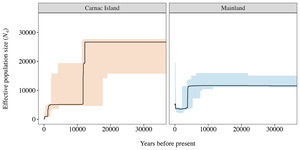

To further investigate the history of tiger snakes on the island, we conducted a follow-up analysis using the genetic data publicly available at BioStudies (Lettoof 2021). It is now possible, using thousands of single-nucleotide polymorphisms from across the genome, to make inferences on the demographic history of a population. This is frequently done by analysing the distribution of allele frequencies in combination with coalescent theory (Liu and Fu 2015). We took the genetic data for the tiger snake populations collected from Carnac Island (n = 9) and across the Swan Coastal Plain (n = 153), and used the Stairway Plot 2 software to estimate changes in effective population size through time (Liu and Fu 2020). We incorporated published estimates of snake mutation rates and generation time to scale the values (Ludington and Sanders 2021), and plotted the results (Figure 1).

With both designated populations, we see generally large and stable populations from roughly 30,000 years ago until after the last glacial maximum (~19,000 years ago). Given a natural origin for the Carnac Island population, we would expect to see a population size drop sometime after the Last Glacial Maximum, when the island would have been separated from the mainland population by post-glacial sea-level rise (roughly 6500 years ago following Playford 1983). Unsurprisingly, we observe a clear reduction in population size during this period (Figure 1), suggestive of a natural origin, contrasting with a later (~4000 years ago) decline in the size of the Swan Coastal Plain population (coinciding with aridification during the mid Holocene (Semeniuk 1986)). We recognise that this analysis is a crude measure of historical demographic inference, with the small sample size of individuals from Carnac Island producing rough estimates of population size, but it would be an unlikely coincidence if the same patterns were observed in a recently established population that was translocated from the mainland.

CONCLUSION

The evidence that some number of tiger snakes were released on Carnac Island in the first half of the 20th century by Rocky Vane is substantial, and we applaud the considerable efforts of Ladyman et al. (2020) and Burbidge (2024) in researching the historical occurrence of tiger snakes on Carnac Island. However, given (1) the distribution of tiger snakes on islands around Australia, (2) evidence of experienced snake ecologists not finding tiger snakes on Carnac Island, (3) knowledge of snake behaviour and detection probability, (4) understanding of mortality rates in translocated snakes, and (5) available population genetic data, we believe it is certainly plausible, and indeed probable, that tiger snakes naturally occupied Carnac Island prior to any putative translocation. Assuming that all historical documentation of snakes on the island has been fully evaluated, we suggest that the only way to confirm or disprove the natural origin hypothesis is to conduct further new analyses (e.g. genetic, gut biomes, parasite relationships). This could include sampling individuals from a larger number of Carnac Island, Garden Island, and southwestern Australian tiger snake populations to further clarify relationships and establish a more complete phylogeographic understanding of the species distribution. While we are reasonably convinced that the tiger snakes of Carnac Island are natural in origin, we certainly agree with many other authors that it would be a marvellous feat of colonisation and evolution if the population was established from a single large translocation event roughly 100 years ago.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our thanks to all the people who contributed to tiger snake surveys, tissue sample collection, and genomic data production over the past 10 years.