[Editor’s Note: Most of the content of this paper was originally archived in unpublished supplementary files to Haig, D.W., Rigaud, S., McCartain, E., Martini, R., Barros, I.S., Brisbout, L., Soares, & J. Nano, J. (2021a). Upper Triassic carbonate-platform facies, Timor-Leste: Foraminiferal indices and tectonostratigraphic association. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 570, article 110362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2021.110362. Some of the unpublished supplementary material is here published with permission from the Senior Copyright’s Specialist, Elsevier, in a pers. comm. to D.W. Haig dated 22 September 2023.]

Introduction

Recent studies in Timor-Leste (Fig. 1) have shown that most massive shallow-water limestone exposed on peaks and mountain ranges and mapped by Audley-Charles (1968) as Lower Miocene “Cablac Limestone” belongs either to the Triassic Bandeira Formation (Haig et al. 2021a; Barros et al. 2022) or to the Lower Jurassic Perdido Limestone (Benincasa et al., 2012; Haig et al. 2021b, 2024; Nano et al. 2023). The “Cablac Limestone” is only one of the many major discrepancies that have been found in Audley-Charles’s (1968) geological mapping (see also papers by McCartain et al. 2006, 2024; Haig and McCartain, 2007, 2010, 2012; Haig et al. 2007, 2008, 2014, 2017, 2019; Haig 2012; Barros et al. 2022, 2025). These discrepancies have significant implications for understanding the tectonic history of Timor Island. Most sedimentary rocks in Timor-Leste are made up of (1) lithogenic grains derived from reworking of older rocks; (2) biogenic particles that are the organic or mineralised skeletal remains mainly of contemporaneous organisms; and (3) a precipitated or recrystallized authigenic component formed within the sediment pile. Much of the mapping done during the last 70 years in Timor has not involved detailed analyses of the biogenic component of the sediment and this has led to major misidentifications of ages and tectonic affinities.

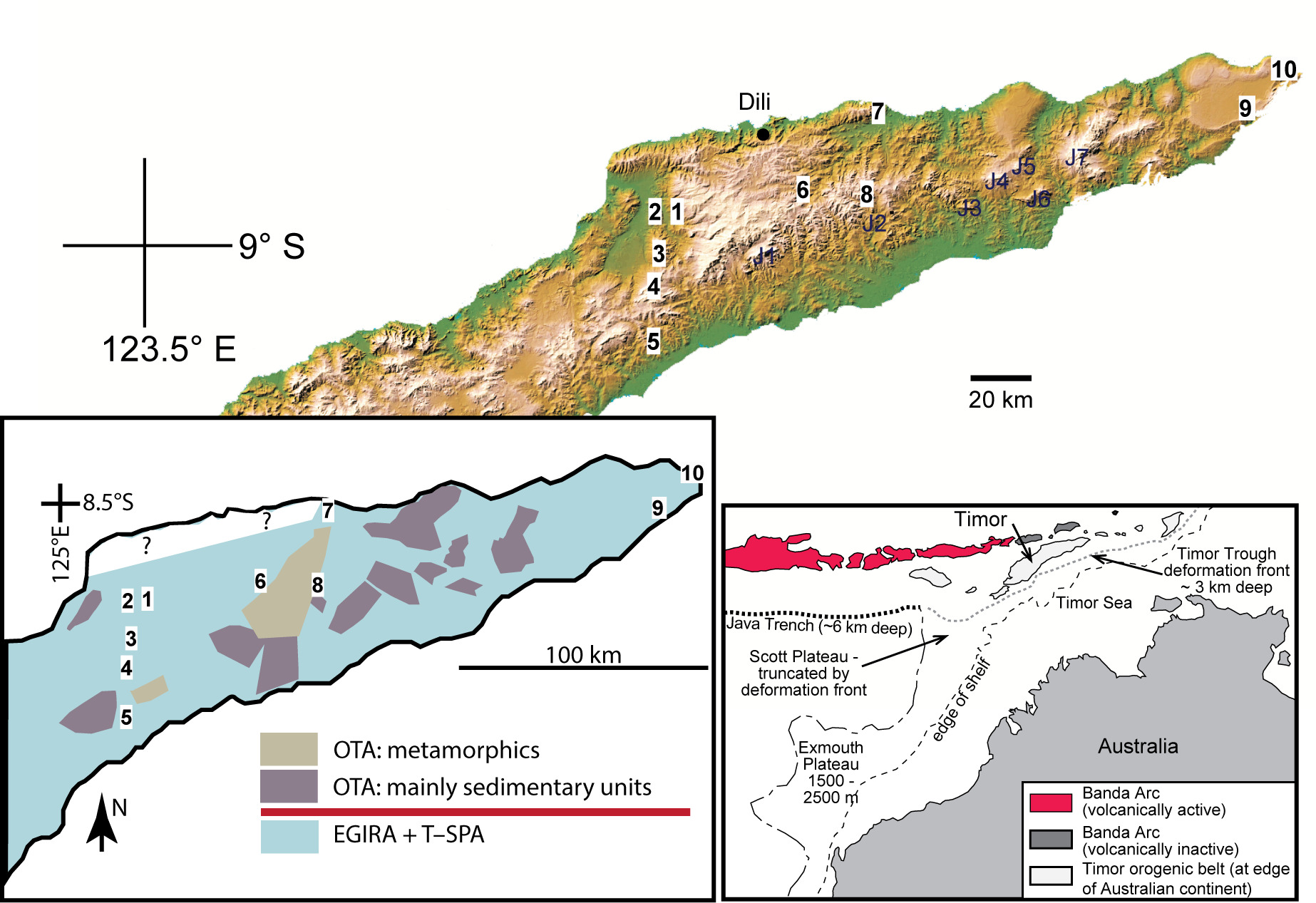

The Bandeira Formation and the Perdido Limestone belong to different tectonostratigraphic associations (Appendix 1), each with a different set of associated geological formations deposited in different tectonic settings (Haig et al. 2019, 2021a, 2021b, 2024; Nano et al. 2023). The Bandeira Formation is part of the East Gondwana Interior Rift Association (EGIRA; Fig. 2), deposited within depocenters along a major interior rift system in the eastern part of Gondwana (Harrowfield et al., 2005; Haig and McCartain 2010; Davydov et al., 2013; Haig et al. 2014, 2015, 2017, 2021a). The rift system also encompassed sedimentary basins to the south of Timor, now along the Western Australian margin. The Perdido Limestone belongs to the Overthrust-Terranes Association (OTA) with a very complex and different tectonic history to the Bandeira Formation (Nano et al. 2023; Haig et al. 2024).

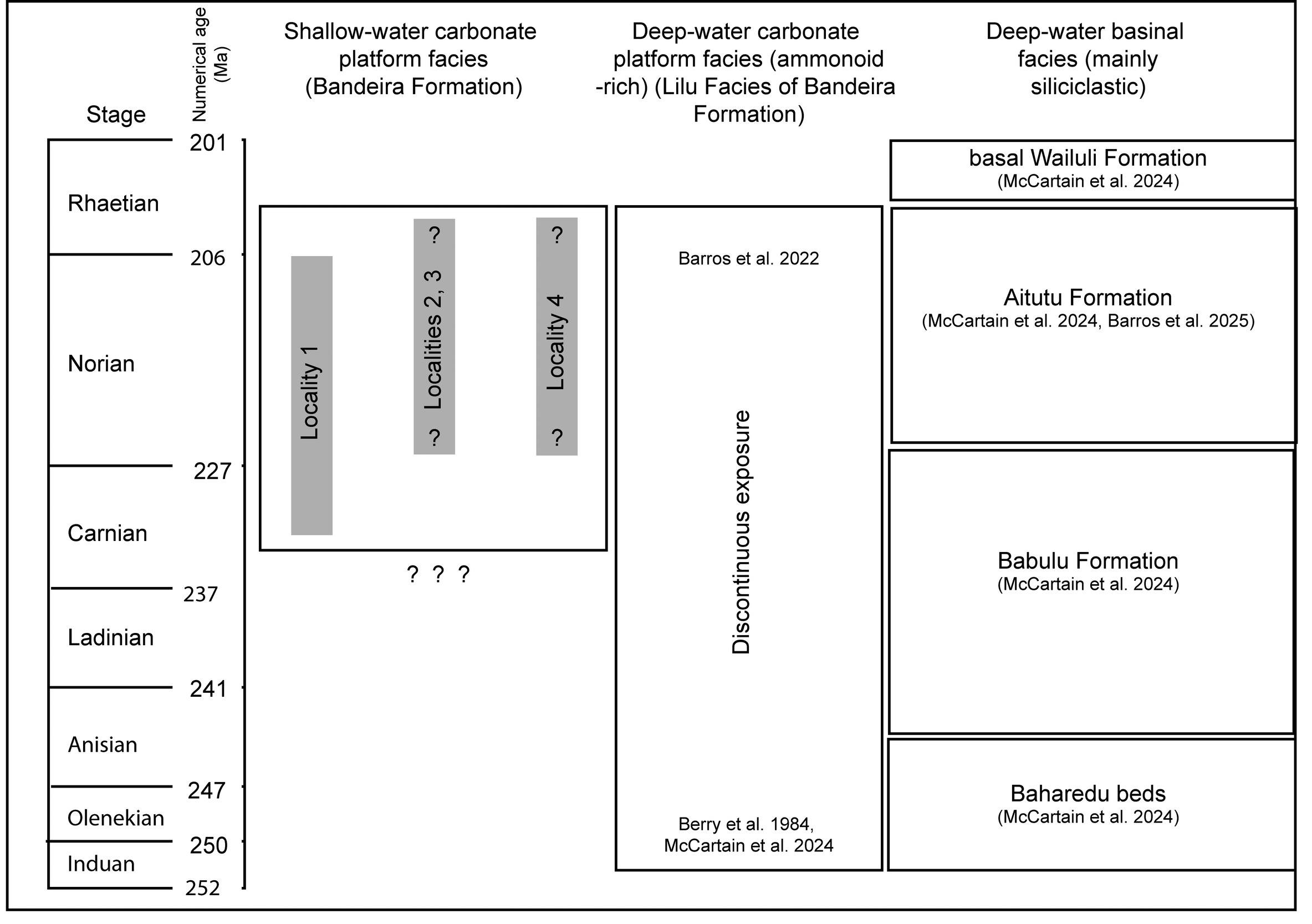

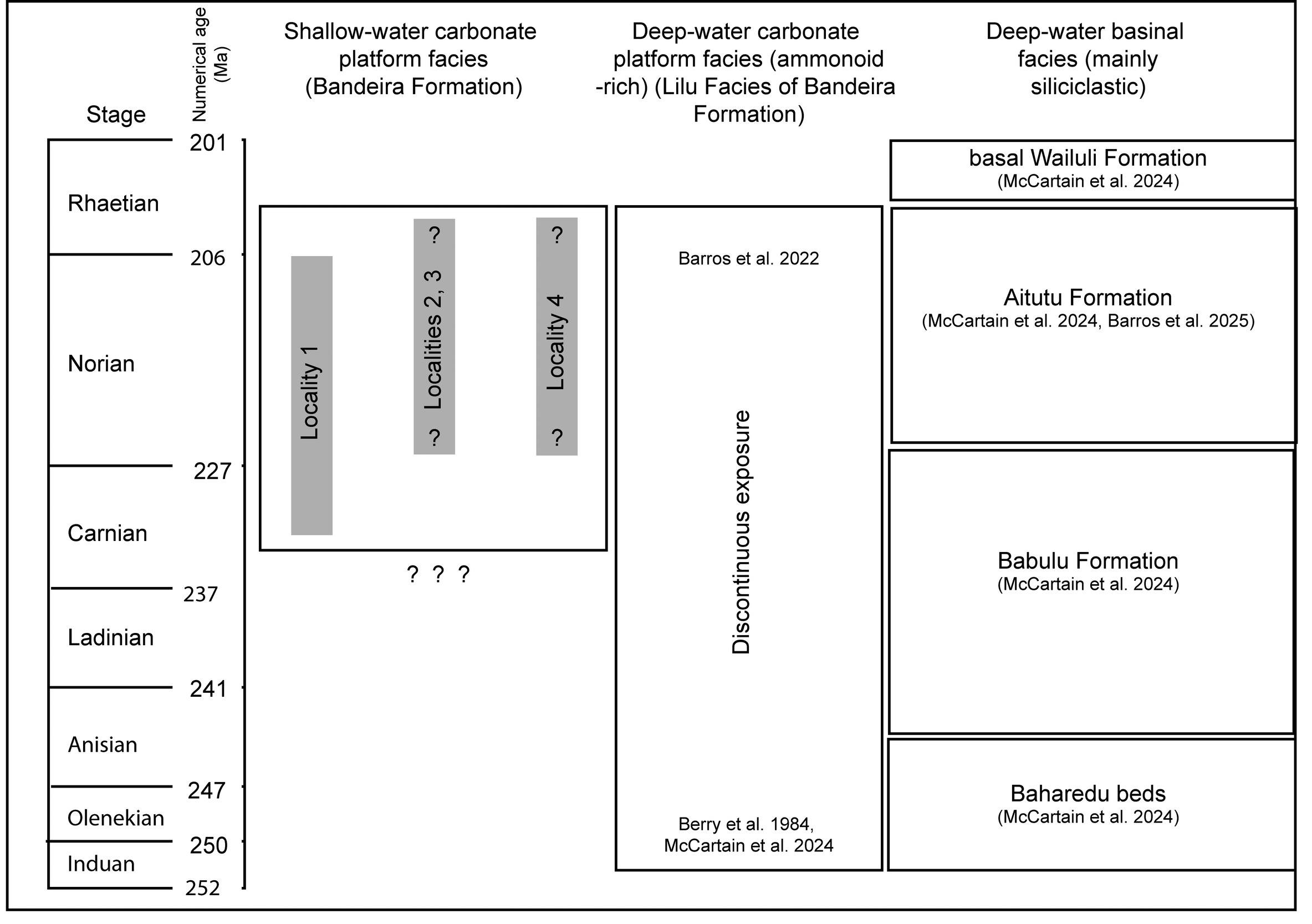

The known age of the Bandeira Formation is from Carnian to within the Rhaetian of the Late Triassic (Haig et al. 2021a, Barros et al. 2022, and this study; Fig. 2). The Perdido Limestone is Sinemurian–Pliensbachian (within the Early Jurassic; Haig et al. 2021b, Nano et al. 2023, Haig et al., 2024). There is no overlap in age range between these formations. The relationships between the Bandeira, Cablac and Perdido limestones shown, for example, by Tate et al. (2015), Duffy et al. (2017), Charlton et al. (2018) and Bucknill et al. (2019) are not supported by documented field observations of stratigraphic relationships nor biostratigraphic or other age analyses.

A general synthesis of the Triassic carbonate-platform deposits in Timor-Leste was presented by Haig et al. (2021a), and the Triassic stratigraphic framework in Timor was outlined in that paper and by McCartain et al. (2024) and is listed in Appendix 1 which summarizes the most recent interpretation of the tectonostratigraphy of Timor-Leste. The present paper provides information on the shallow-marine limestones of the Bandeira Formation at four localities in Timor-Leste recorded by Haig et al. (2021a) with the detailed information originally archived in unpublished supplementary data. In the following text, the stratigraphic setting of each locality as well as information on rock types and fossil assemblages are provided together with the bases for the age determinations. Past stratigraphic designations of the rocks are discussed. The material and methods of the study were outlined by Haig et al. (2021a), and the localities of studied samples are detailed in Appendix 2.

The Triassic shallow-marine limestones attributed to the Bandeira Formation eventually may be designated a “group” subdivided into constituent “formations”. This is because in the type section at Bandeira Gorge, five main units, including the three neritic carbonate sections described here and two shallow-marine siliciclastic intervals, form a conformable succession. Future mapping and biostratigraphic correlative work to determine the lateral extent of each of these units may lead to the recognition of separate formations within a “group”. More detailed facies and sequence stratigraphic analyses of the Bandeira Formation are required at each locality.

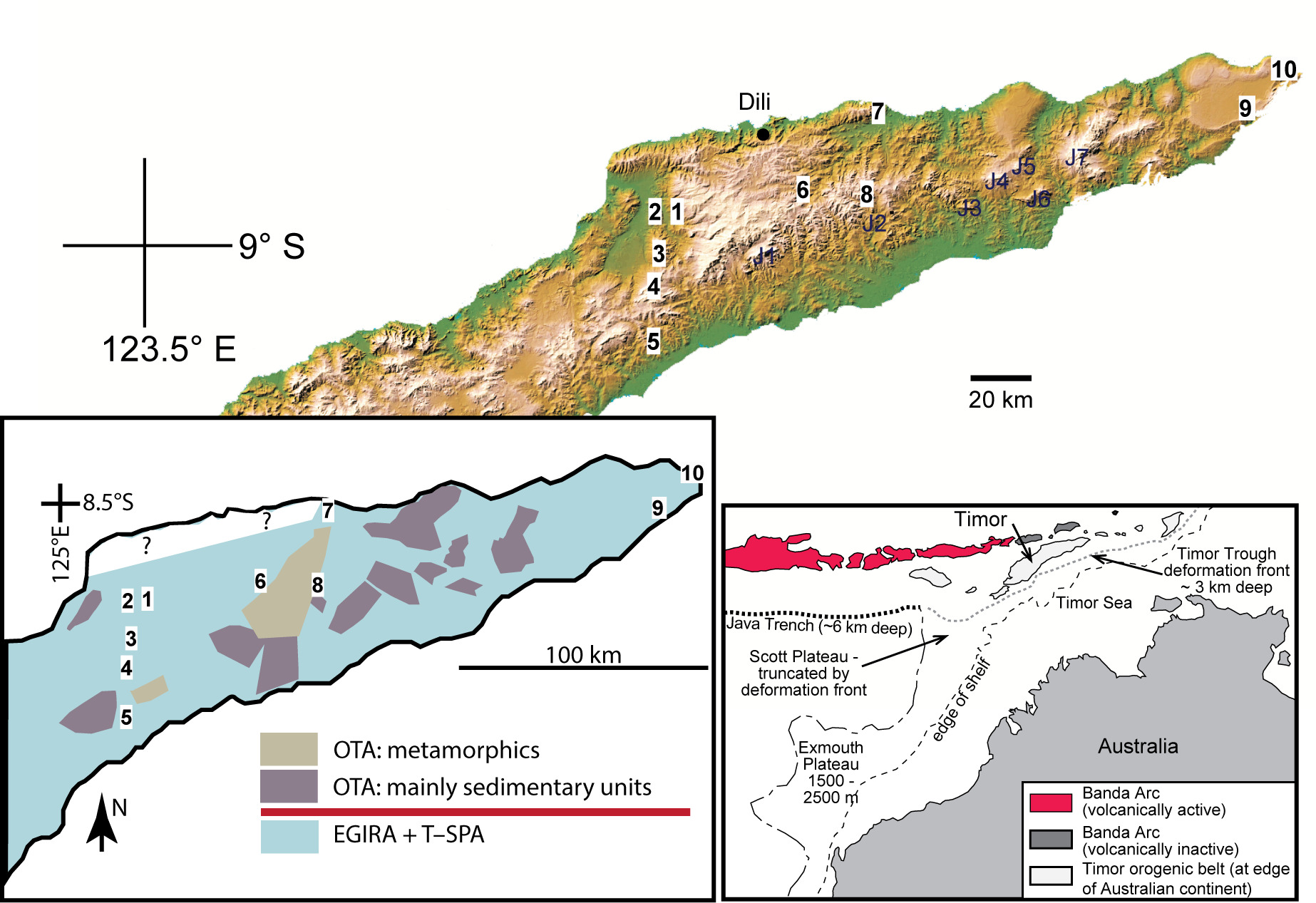

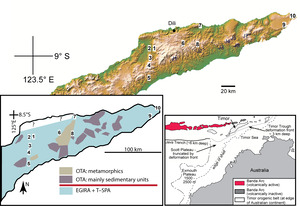

Figure 1.Maps showing the localities of Bandeira Formation limestones discussed in this paper. Top image: SRTM image of Timor (compiled from NASA Shuttle Radar Topography Mission images) showing studied sites of Upper Triassic carbonate-platform facies limestones of the Bandeira Formation: 1, Bandeira Gorge, type section of the Bandeira Formation; 2, Lesululi Fatu; 3, Loelako Fatu; 4, Saburai Range; 5, Lakus Mountain, Weber’s locality 12 recorded in Wanner (1956). Sites 6 to 10 in eastern Timor-Leste will be outlined in a following paper. Carbonate-platform facies of the Lower Jurassic Perdido Group, often confused with the Bandeira Formation or with younger limestone units, are present at localities labelled J1–J7 (see Haig et al. 2021b). Lower left: Schematic map with synorogenic deposits stripped away, showing the distributions of EGIRA and post-breakup Timor–Scott Plateau Association (T–SPA). Also shown are dismembered blocks of OTA that collided with and were emplaced onto the Timor margin of the Australian continent during orogenesis that commenced during the Late Miocene. Lower right: present-day tectonic setting of Timor.

Figure 2.Chronostratigraphic correlation of Triassic formations belonging to the East Gondwana Interior Rift Association in Timor-Leste. At the studied localities, the known stratigraphic range of the Bandeira Formation at each locality lies within the grey rectangles in the left-hand column. Chronometry follows International Chronostratigraphic Chart v2024-12 (www.stratigraphy.org) Locality 1: Bandeira Gorge

A 700 m thick succession exposed on the northern scarp of Bandeira Gorge (Figs. 1, 3) forms the type section of the Bandeira Formation (Haig et al. 2021a). Three limestone units are present: units 1, 3, and 5. Unit 2 is mainly lithic sandstone with thin interbeds of mudstone in its lower part overlain by heterolithic sandstone/mudstone (with changes in dominance of these rock types in different parts of the section) and planar laminated fine sandstone and mudstone. Unit 4 is covered by soil and scree. It is probably a friable sandstone/mudstone section.

_for_location_i.jpeg)

Figure 3.Type area of the Bandeira Formation in Bandeira Gorge (see Fig. 1 for location in Timor-Leste). A, schematic log of a composite type section taken from the northern side of Bandeira Gorge. B, Google-Earth image of the gorge with yellow circles at Unit 1 sampling sites, green circles at Unit 3 sites, blue circles at Unit 5 sites, and orange circles at sites on the southern side of the gorge (see Appendix 2 for locality co-ordinates). C, typical outcrop of Unit 1. D, the contact between Unit 1 and Unit 2 with person standing on contact. E, a section through Unit 3. Unit 1

Rock types sampled

Unit 1 samples examined for this study (Appendix 2) are mainly from thick bedded to massive rudstone/floatstone to coarse grainstone with micritic clasts common in most samples (Fig. 3C, Table 1). Lithoclasts composed of skeletal debris in a micritic matrix are also common. Persistent grain types include foraminifers (particularly involutinid and carbonate-cemented agglutinated/microgranular types), echinoderm debris including echinoid spines and sporadic crinoid plates with occasional columnals displaying pentagonal cross-sections; mollusc debris including microgastropods, recrystallized shell fragments (most from gastropods and bivalves), and bivalve fragments with prismatic microstructure; impunctate and punctate brachiopod shell debris; and ostracods. Less common grains include oncoids, ooids, nodular porostromate calcimicrobes, solenoporacean algal nodules, dasyclad algae, Tubiphytes, calcareous sponges and isolated triaxon sponge spicules, corals, bryozoans, and silicate mineral grains (mainly quartz). The grain assemblage and the massive bedding suggest high-energy depositional conditions in very shallow water. The overlying sandstone beds (Unit 2; Fig. 3A) include large Thalassinoides burrows and have a scoured contact with the limestone, indicating an influx of sand onto a shallow submerged flat.

Foraminifera

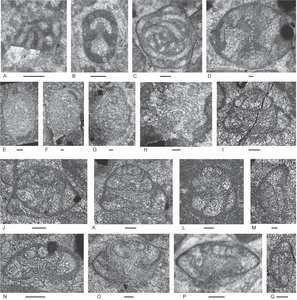

Foraminifers (Figs. 4, 5) are common to rare in the studied samples of Unit 1. Individual species are rare and sporadic in distribution (Table 2). At least forty species comprise the microfauna

Table 1.Main grain constituents in limestones of Unit 1 of the type section of the Bandeira Formation.

| Samples |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Major grain constituents |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| micritic/micritized clasts and peloids |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

| peloids (< 0.2 mm) |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

| ooids |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

| oncoids |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

| reworked shallow-marine limestone clasts |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

| porostromate calcimicrobes |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

X |

| solenoporacean algae |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| dasyclad algae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tubiphytes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| carbonate-cemented agglutinated forams |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

| cornuspirids and ophthalmidiid forams |

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

| involutinid forams |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

| nodosariid (most indeterminant) |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

| vaginulinids (most indeterminant) |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

| robertinid forams |

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

| calcareous sponges |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

X |

X |

| isolated sponge spicules (triaxons) |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| coral |

|

? |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| bryozoans |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| impunctate brachiopods |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

| punctate brachiopods |

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

| recrystallized bivalve fragments |

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

X |

| bivalve fragments with prismatic microstructure |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

| gastropods |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

| indeterminant echinoderm debris |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

| crinoid columnal plates (pentagonal) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| crinoid columnal plates (circular) |

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

| echinoid spines |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

| ostracods |

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

| silicate mineral grains (mainly quartz) |

|

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

Table 2.Foraminifera from Unit 1 of the type section of the Bandeira Formation

| Samples |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Agathammina iranica Zaninetti, Brönnimann, Bozorgnia & Huber |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| Aulotortus sinuosus Weynschenk |

? |

? |

? |

|

|

? |

|

? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

? |

|

X |

| Aulotortus spp. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

| Indeterminant aulotortids |

X |

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

| Austrocolomia marschalli Oberhauser |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Calcivertinelline indeterminant |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cassianopapillaria laghii (di Bari & Rettori) |

|

|

? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cassianopapillaria spp. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cassianopapillariina (either Diplotremina or Cassianopapillaria) |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

? |

|

|

|

|

| Diplotremina altoconica Kristan-Tollmann |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

| Duostomina rotundata Kristan-Tollmann |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Duostomina turboidea Kristan-Tollmann |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Duostominina indeterminant |

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

X |

| Duotaxis metula Kristan |

|

? |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Endoteba ex gr. badouxi (Zaninetti & Brönnimann) |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Endoteba kuepperi Oberhauser |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

? |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

| Endotebanella robusta (Salaj) |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Endotebanella spp. |

|

? |

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

? |

|

? |

? |

| Endotriada cf. tyrrhenica Vachard, Martini, Rettori & Zaninetti |

|

|

? |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

| Endotriadella aff. wirzi (Koehn-Zaninetti), |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| “Everticyclammina” cf. simplex (Urosevic) |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| glutameandratids indeterminant |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

| Hemigordiopsid-like microgranular species |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

? |

| Karaburunia sp. |

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

? |

|

|

|

|

|

| Lamelliconus multispirus (Oberhauser) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

| Lamelliconus ventroplanus (Oberhauser) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

| Malayspirina fontainei Fontaine, Khoo & Vachard |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ophthalmidium sp. |

|

? |

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Palaeolituonella meridionalis (Luperto) |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Parvalamella friedii (Kristan-Tollmann) |

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

? |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

? |

X |

X |

| Parvalamella? praegaschei (Koehn-Zaninetti) |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

| Transitional between P? praegashi and P. fredli |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

| Planiinvoluta carinata Leischner |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

| Prorakusia primigenia di Bari & Laghi |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

? |

| Prorakusia cf. salaji di Bari & Laghi |

X |

X |

? |

|

|

? |

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

| Rectoglomospira cf. senecia Trifonova |

|

|

? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Robertonella sp. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

| Semimeandrospira rauli Urosevic |

|

|

|

? |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| “Siphovalvulina” almtalensis (Koehn-Zaninetti) |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

| “Tolypammina” gregaria (Wendt) |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Triadodiscus eomesozoicus Oberhauser |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

| Trocholina? cordevolica Oberhauser |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

with variable but generally poor preservation. Carbonate-cemented agglutinated (or microgranular) and involutinid types are the most persistent forms, present in at least a third of the samples.

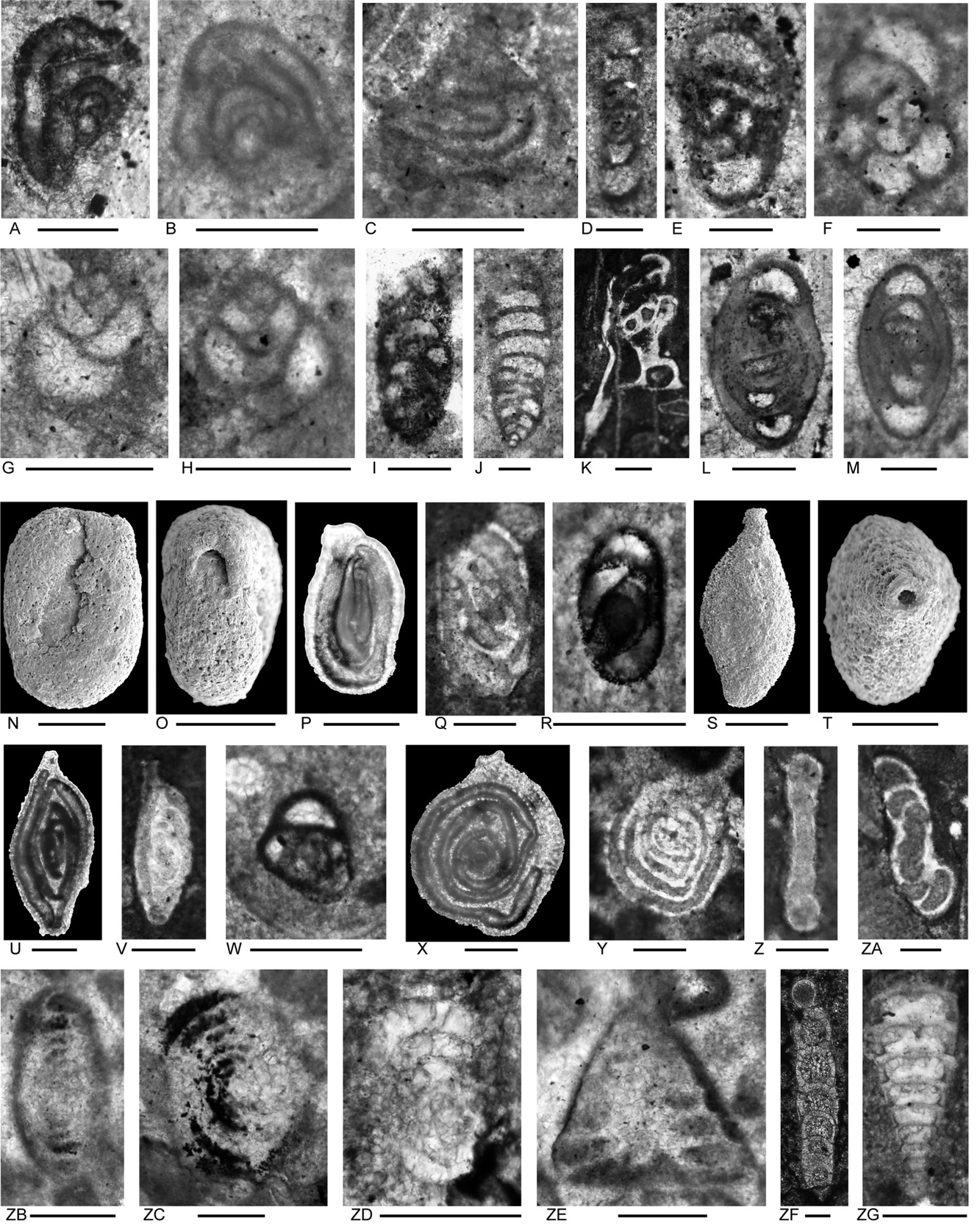

Age

Unit 1 is positioned in the Carnian, probably late Carnian, based on overlap of ranges (see Fig. 8 of Haig et al. 2021a, and Appendix 3): (1) possible Prorakusia primigenia (Fig. 5C), a species known only from the upper Carnian; (2) Prorakusia cf. salaji (Fig. 5D–G), probable Cassianopapillaria laghii (Fig. 5ZD), and Semimeandrospira rauli (Fig. 4W), species probably confined to the Carnian; (3) Duostomina turboidea (Fig. 5Y), Lamelliconus multispirus (Fig. 5N), Lamelliconus ventroplanus (Fig. 5O–Q), Triadodiscus eomesozoicus (Fig. 5A, B) and Trocholina? cordevolica (Fig. 5R), species ranging to the late Carnian; (4) Diplotremina altoconica (Fig. 5ZA–ZC) and Duostomina rotundata (Fig. 5T, U), which do not range lower than Carnian). The presence of common Parvalamella? praegaschei (Fig. 5J–M) in some samples, known from the late Ladinian to Carnian (and possibly Norian) supports the chronostratigraphic placement as does the presence of possible Robertonella (Fig. 5S) that ranges from the late Carnian.

Previous stratigraphic designation and stratigraphic association

Audley-Charles (1968) and Grady and Berry (1977) mapped this part of Bandeira Gorge as Aitutu Formation (see Appendix 1 and definitions in Audley-Charles 1968 and McCartain et al. 2024). No beds of radiolarian-rich carbonate-cemented mudstone (wackestone or calcilutite of some authors), typical of the Aitutu Formation (Audley-Charles 1968, p. 10), have been observed by us in the section. In contrast, Bachei and Situmorang (1994) mapped the area as Cablac Limestone of the Miocene. Tate et al. (2015) mapped the limestone as Permian Maubisse Formation thrusted over “TR-Jw, Triassic-Jurassic” Wailuli Formation. Upstream in the gorge, Audley-Charles (1968) indicated that Permian rocks (now placed in the Maubisse and Cribas groups of the East Gondwana Interior Rift Association, EGIRA; Haig et al., 2014, 2017, 2019) had an overthrust relationship with Triassic strata. We have not observed the structural relationship in the vicinity of the type Bandeira Formation outcrop. However, upstream the Maubisse Group probably outcrops because boulders of the Permian units are common among the river gravel. Downstream from the type section, Audley-Charles (1968) mapped the Wailuli Formation (Appendix 1), but these strata could belong to the Babulu Formation of the Middle to lower Upper Triassic. Audley-Charles (1968) did not recognize the Babulu Group and included many outcrops that we now place in this group as “Wailuli Formation”. Our regional observations confirm that outcrop of the Bandeira Formation at the type section is associated with other units of EGIRA (viz. Wailuli, Babulu and Maubisse groups), and that there is no shallow-water Miocene limestone in the vicinity.

_and_cornuspir.jpeg)

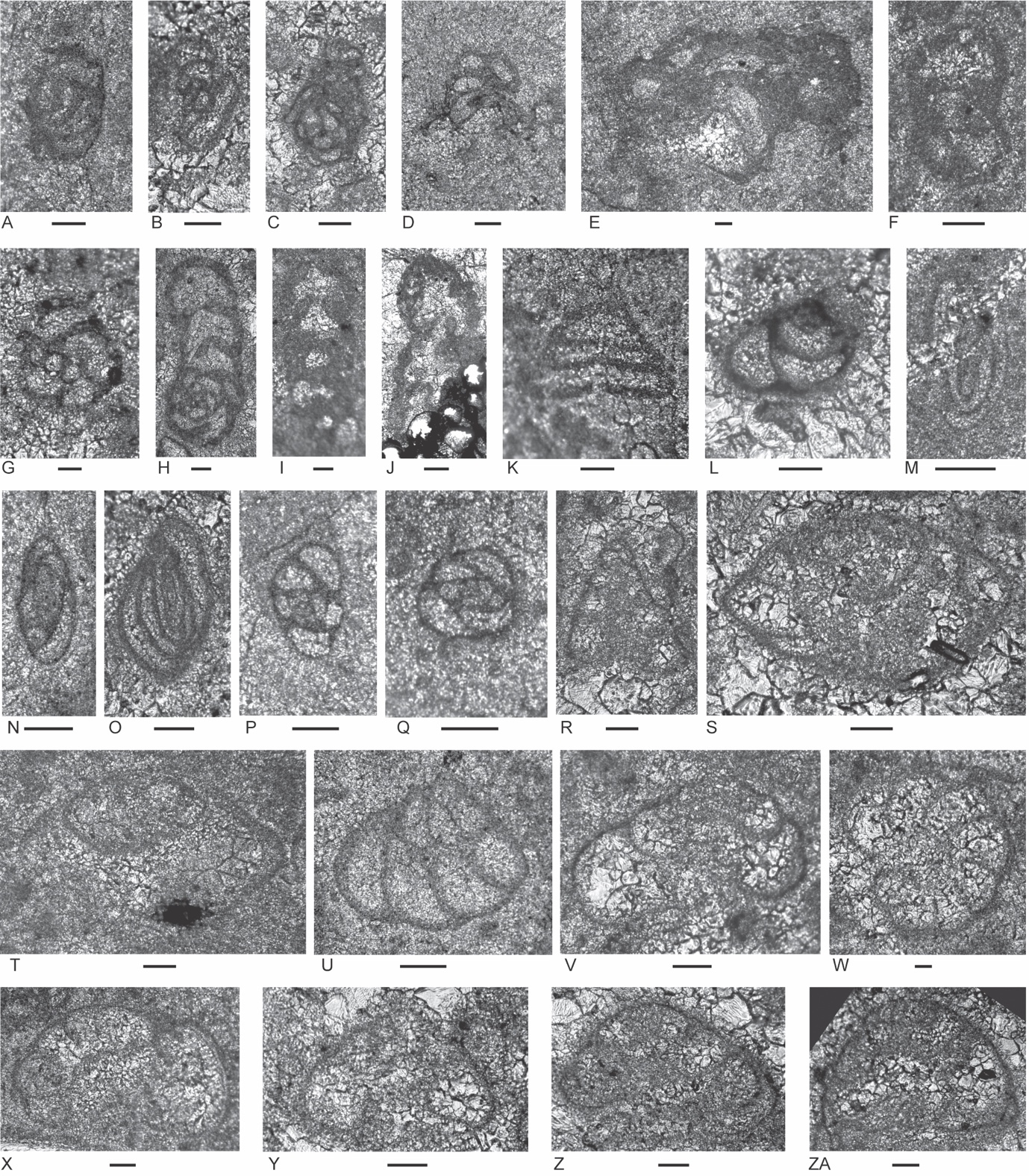

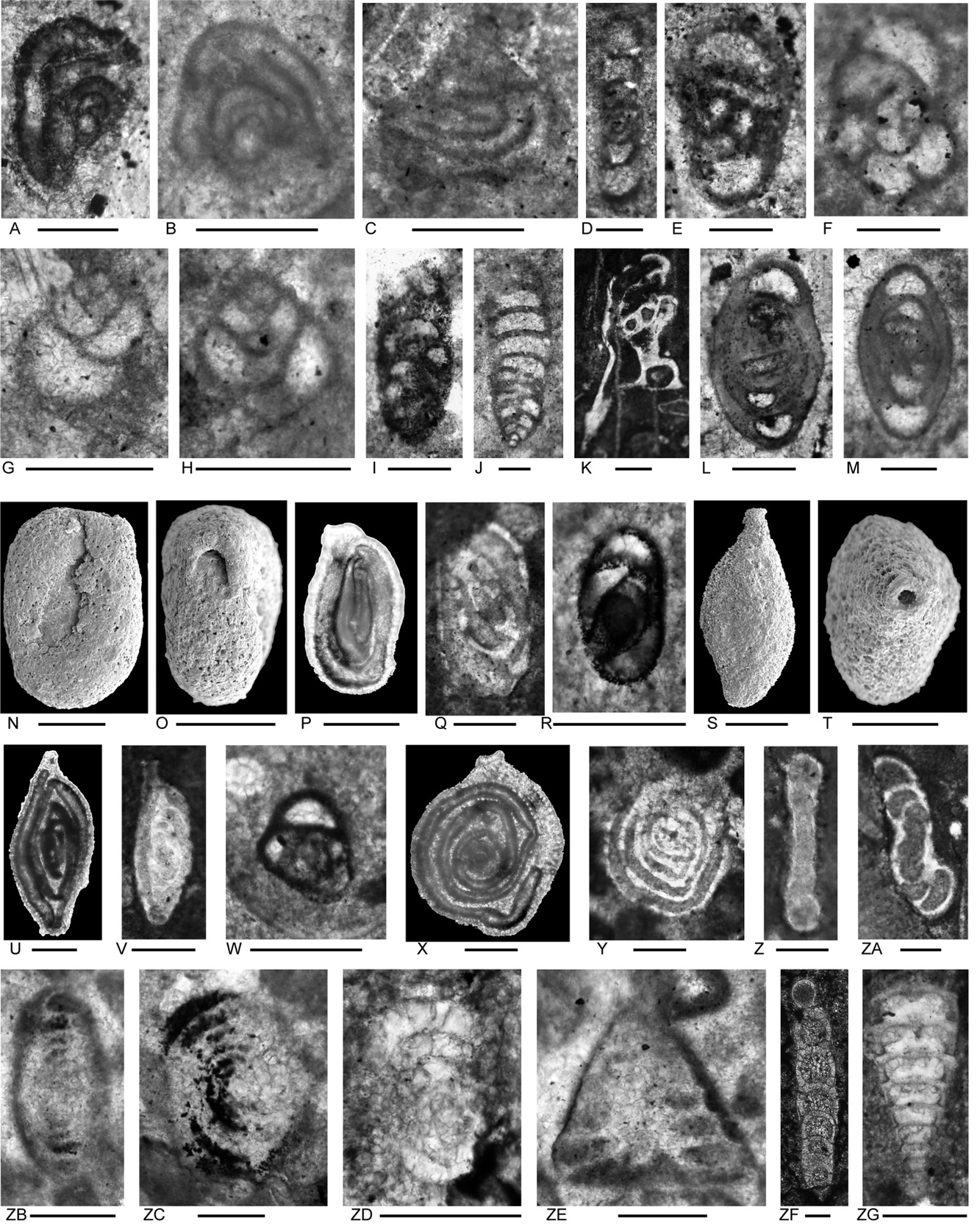

Figure 4.Locality 1 carbonate-cemented agglutinated/microgranular foraminifers (A–S) and cornuspiroids (T–W) from Unit 1 of the Bandeira Formation in Bandeira Gorge (Locality 1, Fig. 1). Bar scale = 0.1 mm unless otherwise indicated. A, B, ? Rectoglomospira cf. senecia Trifonova, from Sample 3. This is not related to Glomospira Rzehak (type species Trochammina squamata Jones and Parker var. gordialis Jones & Parker), nor to other genera within the Ammodiscidae Reuss which are organic-cemented non-calcareous forms. Perhaps related to Pseudoglomospira Bykova (type species Pseudoglomospira devonica Bykova from Upper Devonian, Famennian). C, “Tolypammina” gregaria (Wendt), unrelated to Tolypammina Rhumbler (type species Hyperammina vagans Brady, a modern deep-sea species with a very thin organic-cemented agglutinated test) and to the Tolypammininae Cushman; from Sample 12. Perhaps related to Pseudolituotuba Vdovenko (type species Lituotuba? gravata Conil and Lys; Visean). D, Endoteba ex. gr. badouxi (Zaninetti and Brönnimann), from Sample 3. E–H, Endoteba kuepperi Oberhauser, E and F from Sample 13, G and H from Sample 18. I, Endotriada cf. tyrrhenica Vachard, Martini, Rettori & Zaninetti, from Sample 12. J, Endotebanella robusta (Salaj), from Sample 5. K, ? Malayspirina fontainei Fontaine, Khoo & Vachard, from Sample 8. L, Large test with uncertain chamber arrangement as observed in this section oblique to longitudinal axis and to any plane of biseriality or planispiral coiling; possibly a species of Endotebanella; from Sample 19. M, Endotriadella aff. wirzi (Koehn-Zaninetti), from Sample 3. N, O, Palaeolituonella meridionalis (Luperto), N from, Sample 3, O from Sample 13. P, Q, “Siphovalvulina” almtalensis (Koehn-Zaninetti); see Haig et al. (2007, their table 4) for comparison of holotypes of high to low trochospiral carbonate-microgranular species with inflated chambers and a central umbilical canal, that differ from organic-cemented agglutinated Trochammina Parker & Jones (type species Nautilus inflatus Montagu; see neotype designated by Brönnimann & Whittaker, 1984) which lacks a central umbilical canal and has a different evolutionary history; possibly co-generic with “Siphovalvulina” sensu Boudagher-Fadel et al. (2001) but probably not with Siphovalvulina Septfontaine (type species poorly defined). P from Sample 19; Q from Sample 4. R, S, Duotaxis metula Kristan from Sample 12. T, Planiinvoluta carinata Leischner, from Sample 3. U, Agathammina iranica Zaninetti, Brönnimann, Bozorgnia & Huber, from Sample 4. V, Karaburunia sp. from Sample 8. W, Semimeandrospira rauli Urosevic, from Sample 12. _and_robertinids_(s--zd)_from_unit_1_of_the_ba.jpeg)

Figure 5.Locality 1 foraminifers. Involutinids (A–R) and robertinids (S–ZD) from Unit 1 of the Bandeira Formation in Bandeira Gorge (Locality 1, Fig. 1). Bar scale = 0.1 mm. A, B, Triadodiscus eomesozoicus Oberhauser, A from Sample 19, B from Sample 18. C, Centred axial section of probable Prorakusia primigenia di Bari & Laghi, perhaps with the few final streptospiral whorls broken from the test, from Sample 19. D–G, Prorakusia cf. salaji di Bari & Laghi, D, E, G from Sample 13, F from Sample 18. H, Aulotortus sinuosus Weynschenk, from Sample 19. I, Transitional morphotype between Parvalamella? praegaschei (Koehn-Zaninetti) and Parvalamella friedii (Kristan-Tollmann), from Sample 18. J–M, Parvalamella? praegaschei (Koehn-Zaninetti), J from Sample 18, K–M from Sample 19. N, Lamelliconus multispirus (Oberhauser), from Sample 18. O–Q, Lamelliconus ventroplanus (Oberhauser), O and Q from Sample 19, P from Sample 13. R, Trocholina? cordevolica Oberhauser, from Sample 19. S, Robertonella sp., from Sample 18. T, U, Duostomina rotundata Kristan-Tollmann, from Sample 13. V, indeterminant Duostominina, from Sample 8. W, Cassianopapillaria sp., from Sample 10. X, Cassianopapillariinae; either a species of Diplotremina or Cassianopapillaria; from Sample 12. Y, Duostomina turboidea Kristan-Tollmann, from Sample 3. Z, indeterminant duostominid, from Sample 19. ZA–ZC, Diplotremina altoconica Kristan-Tollmann, like Diplotremina stenocamera He, ZA and ZC from Sample 3, ZB from Sample 13. ZD, ? Cassianopapillaria laghii (di Bari & Rettori), questionable because of poor preservation of probable papillose lamellae, from Sample 3. Unit 3

Rock types sampled

Unit 3 limestone samples (Appendix 2) are mainly wackestone containing scattered skeletal debris (and including some floatstone), as well as peloidal grainstone. Bedding is thin to medium with alternations of wackestone/peloidal grainstone and friable mudstone (Fig. 3E). Besides peloids, the main grain components (Table 3) are foraminifers (see below), ostracods, echinoderm debris (including persistent echinoid spines) and impunctate brachiopod shell fragments. Reworked shallow-marine limestone clasts are rare in few samples as are porostromate calcimicrobes, calcareous sponges, bryozoans, punctate brachiopods, and bivalve fragments. Silicate sand grains (mainly quartz) are present in only one sample. Halobiid bivalve fragments or filaments derived from these have not been found, nor have microgastropods and algae.

Table 3.Major grain constituents of Unit 3 of the type section of the Bandeira Formation

| Samples |

20 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

24 |

25 |

26 |

27 |

28 |

29 |

30 |

31 |

32 |

33 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Major grain constituents |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| micritic/micritized clasts and peloids |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

| peloids (< 0.2 mm) |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

| reworked shallow-marine limestone clasts |

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| porostromate calcimicrobes |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| carbonate-cemented agglutinated forams |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

| cornuspirids and ophthalmidiid forams |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

| involutinid forams |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| nodosariid (most indeterminant) |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

| vaginulinids (most indeterminant) |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

| calcareous sponges |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| bryozoans |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

| impunctate brachiopods |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

| punctate brachiopods |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

| recrystallized bivalve fragments |

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| bivalve fragments with prismatic microstructure |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

| indeterminant echinoderm debris |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

| crinoid columnal plates (circular) |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

| echinoid spines |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

| ostracods |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

| silicate mineral grains (mainly quartz) |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Foraminifera

Among the foraminifers, porcelaneous types are dominant in some samples; carbonate-cemented agglutinated species are sporadic in distribution; nodosariids are rare and involutinids are very rare (Table 4; Fig. 6). Duostominines have not been found. The porcelaneous types are analogous to modern milioline foraminifers that are particularly common in present-day lagoonal facies (Murray, 2006). The lithofacies, including the overall grain assemblage, and the bedding style also suggest that the depositional site of Unit 3 was a normal-marine lagoon with restricted circulation in the bottom waters and a muddy substrate (following models of Flügel, 2004).

Table 4.Foraminifera from Unit 3 of the type section of the Bandeira Formation

| Samples |

20 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

24 |

25 |

26 |

27 |

28 |

29 |

30 |

31 |

32 |

33 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Agathammina iranica Zaninetti, Brönnimann, Bozorgnia & Huber |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Atsabella bandeiraensis Haig & McCartain |

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

? |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

| Aulosina oberhauseri (Koehn-Zaninetti & Brönnimann) |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Aulotortus sinuosus Weynschenk |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Aulotortus spp. |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Austrocolomia marschalli Oberhauser |

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Calcitornella baconica Oraveczné Scheffer |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Duotaxis metula Kristan |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Endoteba spp. |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

? |

|

|

|

|

| Endotriada cf. tyrrhenica Vachard, Martini, Rettori & Zaninetti |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Endotriadella aff. wirzi (Koehn-Zaninetti) |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| glutameandratids indeterminant |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hemigordiopsid-like microgranular species |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hoyenella vulgaris (Ho) |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

? |

|

|

|

|

|

| Karaburunia atsabensis Haig & McCartain |

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

| Karaburunia sp. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ophthalmidium cf. primitivum Ho |

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

| Ophthalmidium sp. |

|

|

? |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Opthalmidiid indeterminant |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Parvalamella sigmoidea Rigaud, Martini & Rettori |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Piallina tethydis Rettori & Zaninetti |

? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| “Siphovalvulina” almtalensis (Koehn-Zaninetti) |

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| “Tolypammina” gregaria (Wendt) |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Trocholina? aff. acuta Oberhauser |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Calcareous agglutinated morphotype with triserial or biserial initial stage then ?uniserial |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

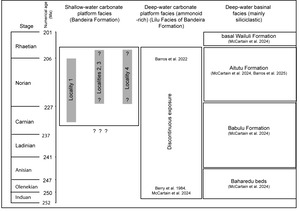

Age

The lagoonal facies of Unit 3 (Locality 1), contains few age-diagnostic foraminifers (see Appendix 3 for ranges and references). Rare Aulosina oberhauseri (Fig. 6ZC), which does not range below the Norian, is present in sample 23 in the upper part of the unit, 69.3 m above base (Appendix 2). A species (Fig. 6ZE in main text) with affinity to Trocholina? acuta, representative of the Norian–Rhaetian, is present with A. oberhauseri in Sample 23. Possible Parvalamella sigmoidea (Fig. 6ZD), a species until now only known from the Norian, is present in sample 27 (position within unit uncertain). Astrocolomia marschalli (Fig. 6ZG), usually reported from the Carnian (Appendix 3) is present in several samples, including 23 and 27, with the Norian indicators.

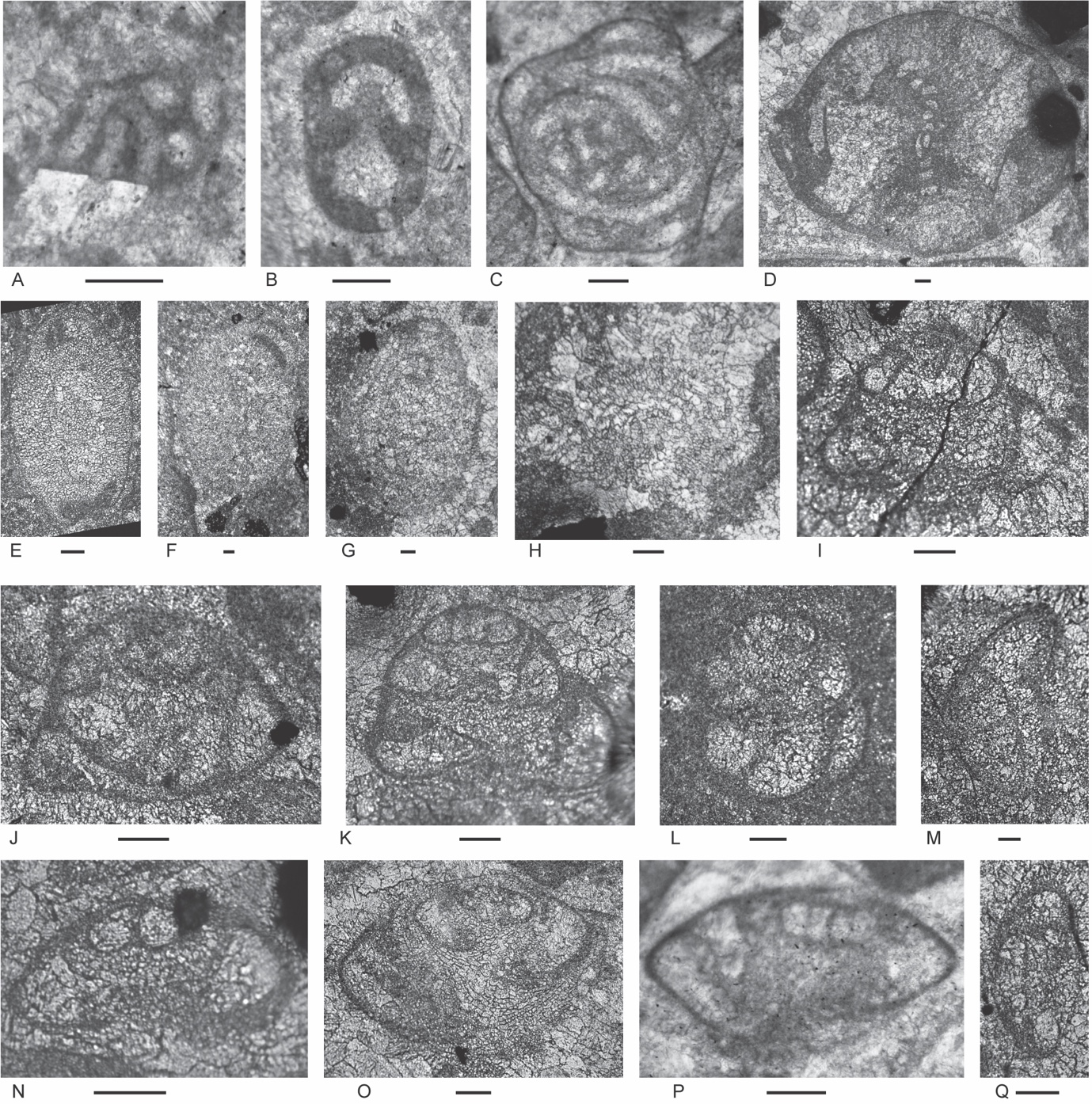

Figure 6.Locality 1, Foraminifera from Unit 3 of the Bandeira Formation at Bandeira Gorge. A–J, carbonate-cemented agglutinated/microgranular species; K–ZA, porcelaneous cornuspiraceans; ZB–ZE, involvutinids; ZF and ZG, nodosariids. Bar scales = 0.1 mm. A–C, Indeterminant glutameandratids, A from Sample 20, B from Sample 21, C from Sample 22. D, Hoyenella vulgaris (Ho), from Sample 23. E, Endoteba sp., from Sample 20. F, Endotriadella aff. wirzi (Koehn-Zaninetti), juvenile test, from Sample 21. G, H, “Siphovalvulina” almtalensis (Koehn-Zaninetti), from Sample 22. I, Indeterminant carbonate-cemented agglutinated species with probable high trochospiral coiling; un-certain because of poor preservation; from Sample 20. J, Indeterminant carbonate-cemented agglutinated species; initial chamber arrangement uncertain but may be triserial although appearing biserial in this off-centred slightly oblique axial section, adult chamber arrangement possibly uniserial, apertural type in adult stage uncertain; not related to the organic-cemented siliceous Gaudryinella Plummer (type species Gaudryinella delrioensis Plummer, Cretaceous); from Sample 21. K, Calcitornella baconica Oraveczné Scheffer, from Sample 21. L, M, Indeterminant involute hemigordiopsid-like species; differs from the type species of Arenovidalina Ho (A. chialingchiangensis Ho, 1959, p. 400, 401, pl. 6, figs 13 holotype, 14–28) by a streptospiral rather than planispiral initial stage; resembles morphotype illustrated by Haig et al. (2018, fig. 4j, from the Lower Permian Fossil Cliff member of the Holmwood Shale in Western Australia, the type level of Hemigordius schlumbergeri (Howchin), the type species of Hemigordius Schubert; L from Sample 20, M from Sample 21. N–R, Atsabella bandeiraensis Haig & McCartain, N–P are free specimens with different views of holotype (N and O) and specimen (P) under glycerine taken in transmitted light, from Sample 33, Q from Sample 22, R from Sample 27. S–W, Karaburunia atsabensis Haig & McCartain, S–U are free specimens with different views of holotype (S and T) and specimen (U) under glycerine taken in transmitted light, from Sample 33, V from Sample 22, W from sample 27. X–Z, Ophthalmidium cf. primitivum Ho, X is a free specimen under glycerine taken in transmitted light, from Sample 33, Y from Sample 23, Z from Sample 22. ZA, Indeterminant ophthalmidiid (?) with evolute sigmoidal coiling, from Sample 22. ZB, Indeterminant involutinid, from Sample 23. ZC, Aulosina oberhauseri (Koehn-Zaninetti & Brönnimann), with strengthenings (see Rigaud et al., 2013) in tubular chamber, from Sample 23. ZD, ? Parvalamella sigmoidea Rigaud, Martini & Rettori, identification uncertain due to poor pres-ervation, from Sample 27. ZE, Trocholina? aff. acuta Oberhauser, from Sample 23. ZF, indeterminate nodosarian, from Sample 25. ZG, Austrocolomia marschalli Oberhauser, from Sample 27.

Previous stratigraphic designation and stratigraphic association

Unit 3 is structurally conformable on sandy mudstone beds of the underlying Unit 2 (Fig. 3A). The contact is exposed at several sites and may be erosional. The contact with overlying Unit 4 is obscured by scree. Previous stratigraphic designations and the regional stratigraphic association are as described for Unit 1. Sample RIL029 of Boger et al. (2017), apparently from the river at the base of the gorge just upstream from the Astabe road crossing, probably is from a mudstone in a slumped block of Unit 3 or from Unit 2. This sample was analyzed, as part of a “Gondwana sequence” suite by Boger et al. (2017, their tables 6, 7) for trace and rare elements and Nd isotopes that distinguished the “Gondwana sequence” of Triassic-Jurassic age from the Aileu Metamorphics and suggested different Pangaean/Gondwanan provinces.

Unit 5

Rock types sampled

Unit 5 limestone samples studied here are rudstone or coarse grainstone (Appendix 2, Fig. 3A). In outcrop the rock is usually massive and in places includes large thick bivalve shells (? megalodonts). Large clasts within the rudstone comprise micritic/micritized rounded limestone, solenoporacean algal nodules, porostromate calcimicrobe nodules, recrystallized bivalve fragments, and rare calcareous sponges and corals (Table 5). Microtubus and bryozoans are present as encrusters on the larger clasts. Also present are peloids, very rare ooids, foraminifers (mainly carbonate-cemented agglutinated types and duostominines), impunctate and less common punctate brachiopod debris, and persistent echinoderm debris (including echinoid spines). This clast assemblage indicates that Unit 5 was deposited in a high-energy, very shallow, normal-marine environment.

Table 5.Major grain constituents of limestone in Unit 5 of the type section of the Bandeira Formation.

| Samples |

34 |

35 |

36 |

37 |

38 |

39 |

40 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Major grain constituents |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| micritic/micritized clasts and peloids |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

| peloids (< 0.2 mm) |

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

| ooids |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

| porostromate calcimicrobes |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

| solenoporacean algae |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

| Microtubus |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| carbonate-cemented agglutinated forams |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

? |

|

| involutinid forams |

|

X |

|

|

|

? |

|

| robertinid forams |

X |

X |

|

X |

? |

X |

|

| calcareous sponges |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| coral |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

| bryozoans |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

| impunctate brachiopods |

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

X |

| punctate brachiopods |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

| recrystallized bivalve fragments |

X |

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

| indeterminant echinoderm debris |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

| crinoid columnal plates (circular) |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

| echinoid spines |

X |

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

| ostracods |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

Foraminifera

The foraminiferal assemblage is less diverse than in units 1 and 3 (Table 6, Fig. 7). In contrast to assemblages from units 1 and 3, duostominines are more common, carbonate-cemented agglutinated/microgranular species are rare, and porcelaneous types are absent as are the Nodosariata.

Table 6.Foraminifera in limestone from Unit 5 of the type section of the Bandeira Formation.

| Samples |

34 |

35 |

36 |

37 |

38 |

39 |

40 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Aulosina oberhauseri (Koehn-Zaninetti & Brönnimann) |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

| Aulotortus communis (Kristan) |

|

cf. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Aulotortus sinuosus Weynschenk |

|

cf. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Aulotortus spp. |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| Cassianopapillariina (either Diplotremina or Cassianopapillaria) |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| Diplotremina subangulata Kristan-Tollmann |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

| Duostominina indeterminant |

X |

X |

? |

|

X |

? |

|

| Endoteba spp. |

X |

X |

? |

? |

? |

|

|

| Endotebanella robusta (Salaj) |

|

|

|

|

|

? |

|

| micritized morphotypes like Gandinella but may be placed in Parvalamella spp. |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| Praereinholdella sp. |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| Rakusia oberhauseri Salaj |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| “Siphovalvulina” almtalensis (Koehn-Zaninetti) |

|

|

|

? |

|

|

|

| Tubular calcareous agglutinated morphotype attached to sand grain, with zigzag-coiling |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

Age

The presence of Aulosina oberhauseri (Fig. 7G, H), Aulotortus cf. communis (Fig. 7E), and Diplotremina subangulata (Fig. 7N–P), suggest a Norian correlation (see Appendix 3 for ranges and references). Rakusia oberhauseri (Fig. 7D), from scant records, seems to be an upper Norian species. The upper Norian (Sevatian)–Rhaetian marker, Triasina hantkeni has not been found here.

Figure 7.Locality 1 foraminifers. Foraminifera from Unit 5 of the Bandeira Formation at Bandeira Gorge (Locality 1, Fig. 1). A–C, carbonate-cemented agglutinated/microgranular species; D–H, involutinids; I–Q, duostominids. Bar scale = 0.1 mm. A, Attached tubular carbonate-cemented/microgranular species., from Sample 35. B, ? Endoteba sp., from Sample 35. C, Morphotype similar in coiling to Gandinella, but test may be micritized and may belong within Parvalamella, from Sample 35. D, Rakusia oberhauseri Salaj, from Sample 35. E, Aulotortus cf. communis (Kristan), from Sample 35. F, Aulotortus cf. sinuosus Weynschenk, from Sample 35.G, Aulosina oberhauseri (Koehn-Zaninetti & Brönnimann), note the clear presence of narrowed lumen delimited by poorly preserved strengthenings (see Rigaud et al. 2013 for details), from Sample 37. H, poorly preserved Aulosina oberhauseri. Note relics of strengthenings (arrows), from Sample 37. I–L, Cassianopapillariinae; either a species of Diplotremina or Cassianopapillaria; from Sample 35. M, Indeterminant Duostominina, from Sample 35. N–P, Diplotremina subangulata Kristan-Tollmann, from Sample 35. Q, Praereinholdella sp., from Sample 35. Previous stratigraphic designation and stratigraphic association

Contacts with underlying and overlying units are obscured. Unit 5 is structurally conformable with the lower units exposed in the section. Previous stratigraphic designations and the regional stratigraphic association are as described for Unit 1.

Other limestone samples from the south side of Bandeira Gorge (Appendix 2) include rudstone and wackestone. Although these contain clast types (Table 7) and foraminiferal assemblages (Table 8) like those of units on the north side of the gorge, the precise correlation to the type succession is uncertain. The south-side limestone exposures have probably been displaced by faulting.

Table 7.Major grain constituents of limestone in Bandeira Formation on the southern side of Bandeira Gorge.

| Samples |

41 |

42 |

43 |

44 |

45 |

46 |

47 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Major grain constituents |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| micritic/micritized clasts and peloids |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

| peloids (< 0.2 mm) |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

| oncoids |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

| porostromate calcimicrobes |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

| solenoporacean algae |

? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| dasyclad algae |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tubiphytes |

|

|

|

|

|

? |

X |

| carbonate-cemented agglutinated forams |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

| cornuspirids and ophthalmidiid forams |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

X |

| involutinid forams |

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

| nodosariid (most indeterminant) |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

| vaginulinids (most indeterminant) |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| robertinid forams |

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

| calcareous sponges |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

| isolated sponge spicules (triaxons) |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| bryozoans |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

| impunctate brachiopods |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

| punctate brachiopods |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

| recrystallized bivalve fragments |

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

| bivalve fragments with prismatic microstructure |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

| gastropods |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

| indeterminant echinoderm debris |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

| crinoid columnal plates (circular) |

X |

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

| echinoid spines |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

| ostracods |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Table 8.Foraminifera from limestone in Bandeira Formation on the southern side of Bandeira Gorge.

| Samples |

41 |

42 |

43 |

44 |

45 |

46 |

47 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Aulotortus spp. |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

| Indeterminant aulotortids |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

| Diplotremina altoconica Kristan-Tollmann |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

| Duostominina indeterminant |

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

| Endoteba spp. |

|

|

? |

? |

|

X |

X |

| Endotebanella robusta (Salaj) |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

| Endotriada cf. tyrrhenica Vachard, Martini, Rettori & Zaninetti |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

| glutameandratids indeterminant |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

| Lamelliconus ventroplanus (Oberhauser) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

? |

| Ophthalmidium sp. |

|

|

|

|

? |

|

X |

| Parvalamella friedii (Kristan-Tollmann) |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

| Parvalamella? praegaschei (Koehn-Zaninetti) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

| Planiinvoluta carinata Leischner |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

| Prorakusia cf. salaji di Bari & Laghi |

|

|

? |

|

|

|

|

| Semimeandrospira rauli Urosevic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

| “Siphovalvulina” almtalensis (Koehn-Zaninetti) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

| “Tolypammina” gregaria (Wendt) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

? |

Localities 2 and 3: Lesululi and Loelako fatus

Detailed logging of the contiguous Lesululi and Loelako fatus (Fig. 8) and geological mapping on a fine scale around the fatus has not been undertaken. The recognition of the Bandeira Formation is based on spot samples, as outlined by Benincasa (2015) and reconnaissance mapping. Seven of these samples have been selected to characterize the foraminiferal fauna of the Bandeira Formation forming the mountainous spine of Loelako Fatu (Appendix 2) as well as four samples from the associated Lesululi Fatu to the north. The Bandeira Formation on the fatus is formed of well-bedded to massive, grey to white, fossiliferous wackestone, floatstone and bindstone (Benincasa 2015).

Rock types sampled

In the Loelako samples (Appendix 2), micritic clasts are present in every sample and other persistent grain types (Table 9; recorded in order of decreasing persistence) include impunctate brachiopods, carbonate-cemented agglutinated/microgranular foraminifers, echinoderm debris, ostracods, porostromate calcimicrobes, punctate brachiopods, recrystallized bivalve fragments, gastropods and echinoid spines. Grain types with more scattered abundance are reworked shallow-marine limestone clasts, solenoporacean algae, Microtubus encrustations, ophthalmidiid, involutinid, nodosariid, vaginulinid and robertinid foraminifers, calcareous sponges, bryozoans, bivalve filaments (probably derived from halobiids), ammonoids, and crinoid columnals. A similar distribution is observed in the Lesululi samples except that nodosariid and/or vaginulinid foraminifers occur in each sample. Calcareous sponges and bryozoans are present in three of the four samples, and dasycladacean algae, corals and isolated sponge spicules not found in the Loelako samples are present in at least one of the Lesululi samples (Table 9).

_for_locations_wit.jpeg)

Figure 8.Localities 2, 3, 4 and 5 of the Bandeira Formation (see Fig. 1 for locations within Timor-Leste). A, Google-Earth image showing the positions of Lesululi Fatu (Locality 2), Loelako Fatu (Locality 3), Saburai Mountain (Locality 4), and Webber’s locality 12 on Lakus Mountain (recorded by Wanner, 1956; Locality 5 of this study). Sample sites of this study are shown by yellow circles (see Appendix 2 for precise locality co-ordinates). Also shown is the position of Locality 1 (type locality of the Bandeira Formation). Areas of the Overthrust Terrane Association (OTA) are present around Mt Taroman and Lolatoi. B, view looking north-west toward Loelako Fatu with steeply dipping slab of Bandeira Formation limestone along spine, and areas of basinal Triassic units (Babulu and Aitutu groups) immediately adjacent the fatu. C, view looking west toward Loelako Fatu (to the left) and the lower Lesululi Fatu (to the right). Table 9.Major grain constituents of limestone in Bandeira Formation at localities 2 (Lesululi), 3 (Loelako) and 4 (Saburai).

|

Loelako |

|

Lesululi |

|

Saburai |

| Samples |

135 |

136 |

137 |

138 |

139 |

140 |

141 |

|

142 |

143 |

144 |

145 |

|

146 |

147 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Major grain constituents |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| micritic/micritized clasts and peloids |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

| oncoids |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| reworked shallow-marine limestone clasts |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| porostromate calcimicrobes |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

| solenoporacean algae |

|

? |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| dasyclad algae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Microtubus |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

| carbonate-cemented agglutinated forams |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

| cornuspirids and ophthalmidiid forams |

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

| involutinid forams |

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

? |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

| nodosariid (most indeterminant) |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

| vaginulinids (most indeterminant) |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| robertinid forams |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

| calcareous sponges |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

| isolated sponge spicules (triaxons) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| coral |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

? |

X |

|

? |

|

|

? |

| bryozoans |

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

| impunctate brachiopods |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

| punctate brachiopods |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

| recrystallized bivalve fragments |

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

| bivalve fragments with prismatic microstructure |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| bivalve filaments (probably derived from halobids) |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| gastropods |

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

| ammonoids |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| indeterminant echinoderm debris |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

| crinoid columnal plates (circular) |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

? |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

| echinoid spines |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

X |

| ostracods |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

Foraminifera

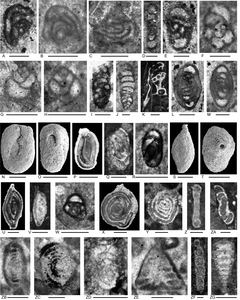

All major groups of Upper Triassic foraminifers are present in the samples (Table 10) with variable preservation making identification difficult. The Lesululi fauna (Table 10, Fig. 9) includes "Tolypammina" gregaria, Endotebanella cf. kocaeliensis, “Everticyclammina” cf. simplex, and Diplotremina subangulata. Hoyenella vulgaris, Duotaxis metula, Aulotortus sinuosus and Diplotremina subangulata are present in assemblages from the Loelako samples (Table 10, Fig. 10).

Table 10.Foraminifera from limestone in Bandeira Formation at localities 2 (Lesululi), 3 (Loelako), and 4 (Saburai).

|

Loelako |

|

Lesululi |

|

Saburai |

| Samples |

135 |

136 |

137 |

138 |

139 |

140 |

141 |

|

142 |

143 |

144 |

145 |

|

146 |

147 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Aulotortus communis (Kristan, 1957) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

| Aulotortus sinuosus Weynschenk, 1956 |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

? |

| aff. Aulotortus sinuosus (with strengthenings in final chambers) |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Aulotortus spp. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

X |

X |

| Indeterminant aulotortids |

|

|

|

|

|

|

? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

? |

X |

| Cassianopapillariina (either Diplotremina or Cassianopapillaria) |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

| Diplotremina subangulata Kristan-Tollmann, 1960, |

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

| Duostominina indeterminant |

|

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

| Duotaxis metula Kristan, 1957 |

? |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

| Duotaxis nanus (Kristan-Tollmann, 1964) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

? |

|

|

|

|

| Endoteba spp. |

|

|

|

|

|

? |

|

|

? |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

| Endotebanella cf. kocaeliensis (Dager, 1978) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

| Endotebanella robusta (Salaj, 1978) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

| Endotebanella spp. |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

| “Everticyclammina” cf. simplex (Urosevic, 1981) |

|

? |

|

|

|

? |

|

|

X |

|

|

? |

|

|

X |

| micritized morphotypes like Gandinella but may be placed in Parvalamella spp. |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

| glutameandratids indeterminant |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

| Hoyenella vulgaris (Ho, 1959), |

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Karaburunia sp. |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

? |

? |

|

|

|

| Parvalamella friedii (Kristan-Tollmann, 1962) |

|

? |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

| Rectoglomospira cf. senecia Trifonova, 1978 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

? |

|

|

|

X |

| “Siphovalvulina” almtalensis (Koehn-Zaninetti |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| “Tolypammina” gregaria (Wendt 1969) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

Age

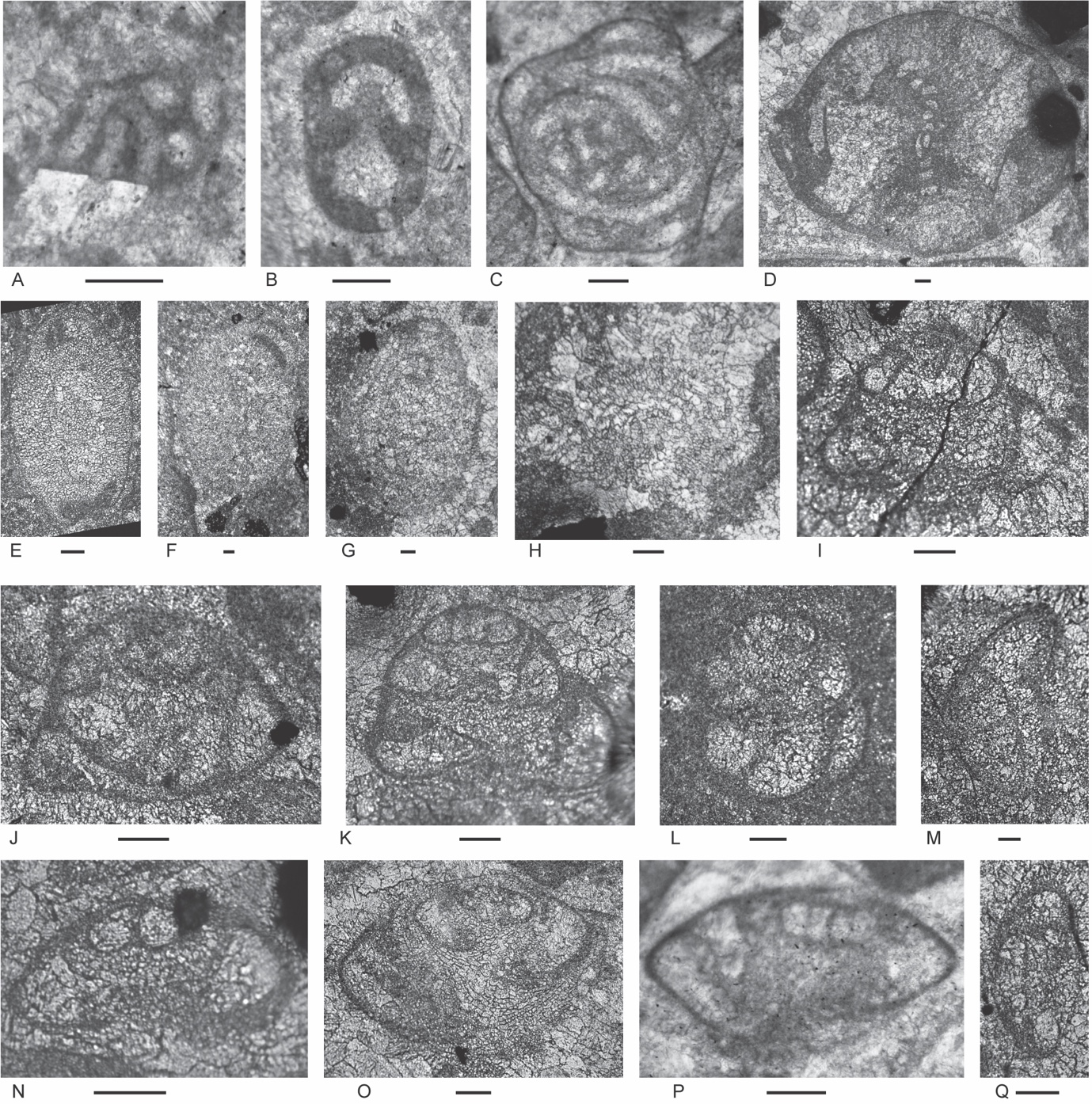

In samples from both Lesululi and Loelako fatus, the presence of Diplotremina subangulata (Figs. 9S, T; 9P, Q, S) indicates a stratigraphic position no lower than Norian (see Appendix 3 for ranges and references). The observed fauna lacks the distinctive involutinids of Unit 1 of the type area in Bandeira Gorge that signify a Carnian age. In one Loelako sample (140), involutinid morphotypes related to Aulotortus sinuosus, but with strengthenings in the final whorls (Figs. 10K, M) are found which appear like specimens illustrated by de Castro (1990) from the Rhaetian of Salerno, Italy, and by Martini et al. (2004) from the Rhaetian of Seram. These may indicate that the Bandeira Formation ranges into the Rhaetian in these fatus.

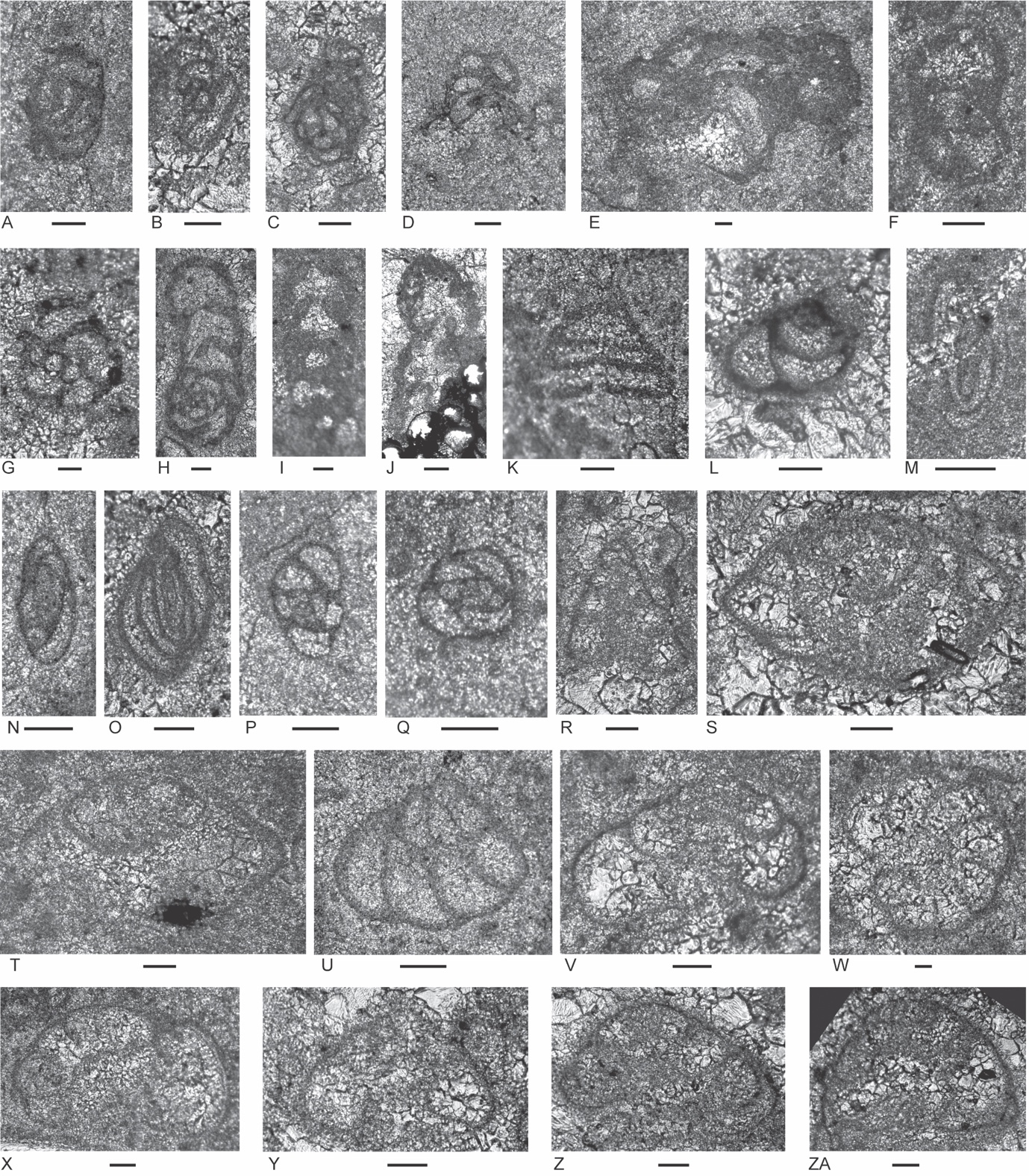

Figure 9.Foraminifers from the Bandeira Formation in the Lesululi Fatu area (Locality 2, Figs. 1, 8). Bar scale = 0.1 mm. A, indeterminant species with glomospire coiling, from Sample 144. B, C, indeterminant, probably glutameandratids, from Sample 145. D, E, “Tolypammina” gregaria (Wendt); see Fig. 4C for discussion on the generic designation; D from Sample 144, E from Sample 144. F, ? Endoteba sp.; uncertain because of poor preservation; from Sample 142. G, H, Endotebanella cf. kocaeliensis (Dager); G, initial coil with aperture apparently in a slightly areal position in the terminal face; H, adult test; differs from E. kocaeliensis by larger test size at 3-uniserial chamber stage, and by having more strongly arched uniserial chambers; from Sample 145. I, Endotebanella sp., from Sample 142. J, “Everticyclammina” cf. simplex (Urosevic), from Sample 142. K, L, indeterminant; possibly Duotaxis; K from Sample 144, L from Sample 145. M–Q, indeterminant ophthalmidiids with milioline coiling, M from Sample 145, N from Sample 142, O from Sample 144, P from Sample 145, Q from Sample 144. R, ? Duotaxis nanus (Kristan-Tollmann), from Sample 144. S, T, Diplotremina subangulata Kristan-Tollmann, S from Sample 145, T from Sample 144. U, indeterminant Duostominina, tangential section, has high spire and few chambers per whorl of D. alta, but details of the umbilical side are not apparent; from Sample 144. V, X–ZA, Diplotremina sp., V and Y–ZA from 145, X from144. W, indeterminant Duostominina, from Sample 144. )._ba.jpeg)

Figure 10.Foraminifers from the Bandeira Formation, Loelako Fatu (Locality 3, Fig. 1). Bar scale = 0.1 mm. All sections from Sample 140, except F–H from Sample 135. A, Hoyenella vulgaris (Ho). B, although resembling species of the agglutinated/microgranular Gandinella kuthani (Salaj), the wall is probably micritized and this test may be better placed in Parvalamella sp. C, Endoteba or Endotebanella sp. D, Endotebanella sp. E, Duotaxis metula Kristan. F, G, Karaburunia sp. H, indeterminant; uncertain if agglutinated or an ophthalmidiid. I, J, Aulotortus sinuosus Weynschenk. K–M, indeterminant involutinids; K (oblique section); L and M have strengthenings in some of the adult whorls. Similar morphotypes were described from the Rhaetian of Salerno, Italy by de Castro (1990) and from the Rhaetian of Seram by Martini et al. (2004). N, indeterminant Duostominina. P, Q, S, ?O, ?R, ?T, Diplotremina subangulata Kristan-Tollmann. U, ? Cassianopapillariinae. Previous stratigraphic designation and stratigraphic association

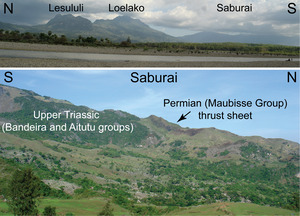

Grunau (1957) mapped the fatus as “Calcários de Fato de idade indeterminada, em parte triásicos” and Gageonnett & Lemoine (1958) designated the ridge formed by the fatus as “Calcaires Fatu (Complexe Charrie)” surrounded by the Autochtone “Mésozoïque”. A very different interpretation was made by Audley-Charles (1968) who mapped the fatus as Cablac Limestone of early Miocene age and showed the mountainous ridge surrounded by Miocene Bobonaro Scaly Clay. This interpretation, although followed by many subsequent authors, was refuted by Benincasa (2015) who recognized that a slab of Bandeira Formation, dipping at a high angle on Loelako Fatu (Fig. 3B) formed the spine of the ridge with Babulu Formation (Middle to Upper Triassic) on the western side of the mountain and Aitutu Formation (Upper Triassic) on the eastern side. The Bandeira Formation forms part of EGIRA in this area.

Locality 4: Saburai Range

Rock types sampled