[Editor’s Note: Most of the content of this paper was originally archived in unpublished supplementary files to Haig, D.W., Rigaud, S., McCartain, E., Martini, R., Barros, I.S., Brisbout, L., Soares, & J. Nano, J. (2021a). Upper Triassic carbonate-platform facies, Timor-Leste: Foraminiferal indices and tectonostratigraphic association. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 570, article 110362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2021.110362. Some of the unpublished supplementary material is here published with permission from the Senior Copyright’s Specialist, Elsevier, in a pers. comm. to D.W. Haig dated 22 September 2023.]

INTRODUCTION

Following Haig et al.'s (2025) account of the Bandeira Formation in western Timor-Leste, limestone deposits from five regions (Sites 6–10; Fig. 1) in eastern Timor-Leste are described in this paper. The tectonostratigraphic affinity of the Bandeira Formation within the East Gondwana Interior Rift Association (Appendix 2) was discussed by Haig et al. (2021a; 2025). The stratigraphic setting, rock types, grain composition, and foraminiferal assemblages found in the limestones are outlined here together with the bases for age determinations and placement in the Bandeira Formation. Previous stratigraphic determinations for the outcrops are discussed. The materials and methods of the study were outlined in Haig et al. (2021a) and the localities of studied samples are detailed in Appendix 3.

Locality 6: Turiscai region

Rock types sampled

Five limestone samples from Locality 6 on the Daisoli River, about 8 km north-west of Turiscai, were examined (Figs. 2, 3; Appendices 2, 3). This material includes three coarse grainstone samples and two samples of calcimicrobe floatstone with a peloidal packstone to wackestone matrix. Clast types that are present in all samples include peloids, porostromate calcimicrobes, involutinid and robertinid (mainly duostominine) foraminifers, gastropods and indeterminant echinoderm debris. Other grains present include possible dasycladacean algae, Microtubus encrustations, carbonate-cemented agglutinated/microgranular foraminifers, calcareous sponges, punctate brachiopods, recrystallized bivalve fragments and fragments with prismatic microstructure, and echinoid spines. In the presence of involutinid and duostominine foraminifers, calcimicrobes, echinoid debris, calcareous sponges, and punctate brachiopods, and possible dasycladacean algae, the rock types resemble those of Unit 1 of the type section of the Bandeira Formation (Haig et al. 2025, locality 1). The duostominines are confined to the Triassic.

Foraminifera

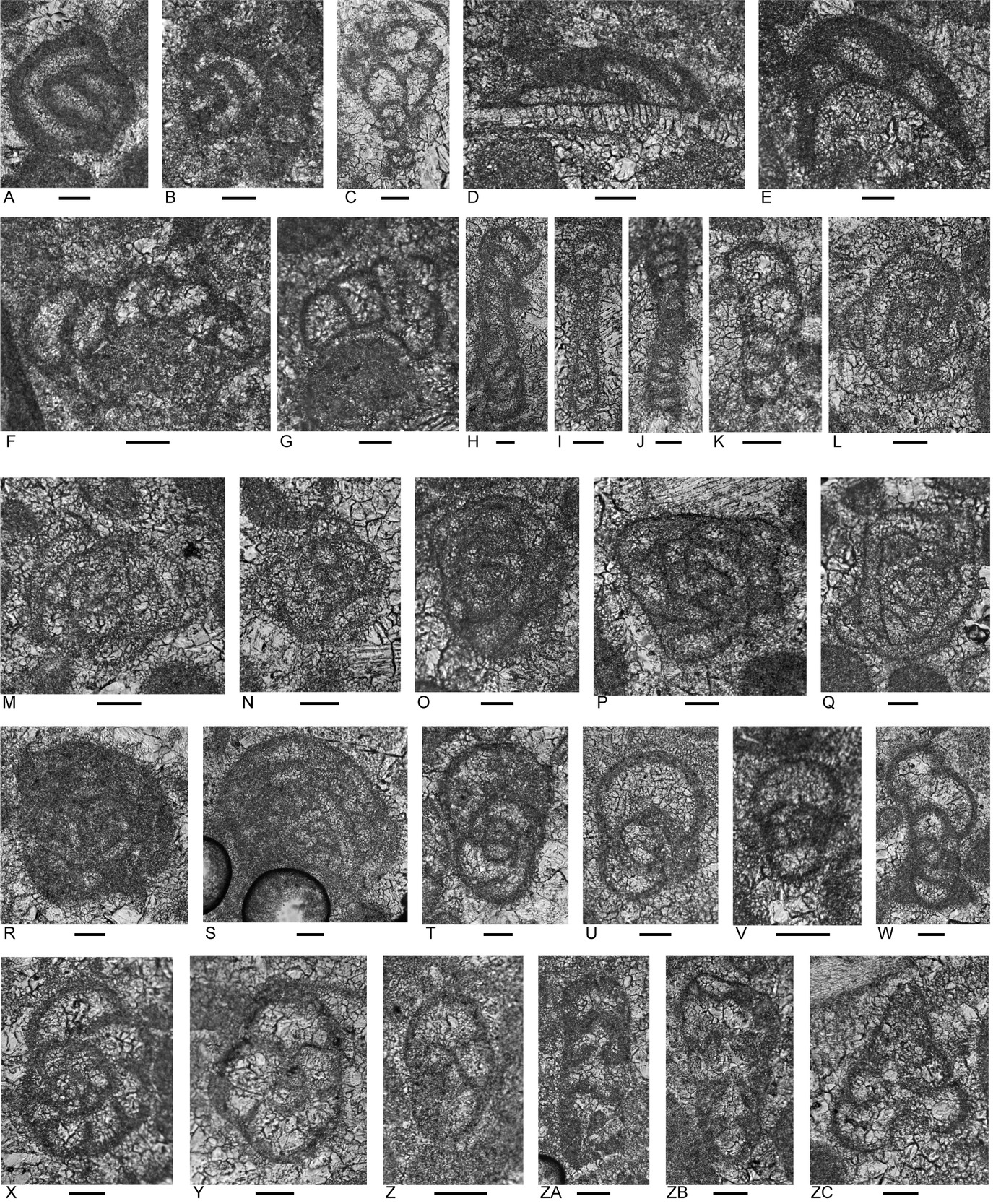

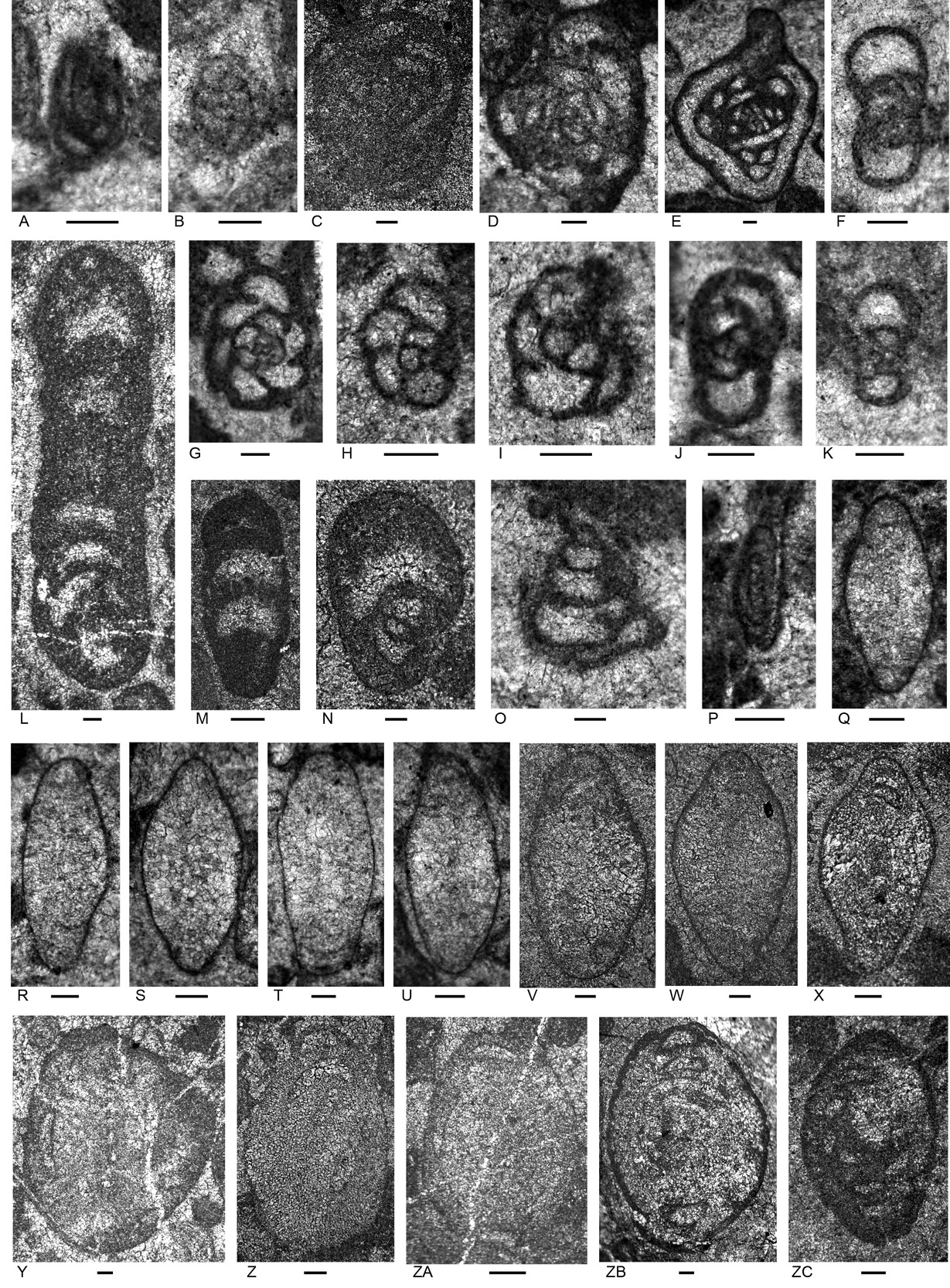

Foraminifers (Fig. 3; Appendix 4) are represented by few species. The tests are partly recrystallized and belong mainly to involutinids and duostominines. Genera include the involutinids Aulotortus (Fig. 3I–Q,S,T) and Parvalamella (Fig. 3R,U), the duostominines Cassianopapillaria (Fig. 3W) and Duostomina (Fig. 3X,Y) and micritized morphotypes that may be either the carbonate-cemented Gandinella or the involutinid Parvalamella (Fig. 3C–H).

Age

The assemblage contains none of the involutinid and duostominine species collectively indicative of the Carnian that are present in Unit 1 at the type locality of the Bandeira Formation (Haig et al. 2021a, 2025). Based on stratigraphic ranges outlined in Appendix 5, Aulotortus sinuosus indicates a broad correlation within the Anisian–Rhaetian and Parvalamella friedii within the Ladinian–Rhaetian. As in samples from the Loelaco Fatu and the Iralalaru #1 borehole section, an un-named morphotype is present that is close to Aulotortus sinuosus but with “strengthenings” (see Rigaud et al. 2013) in the final whorls. Similar morphotypes are known from the Rhaetian of Italy (de Castro 1990) and Seram (Martini et al. 2004). The age here is within the Norian to Rhaetian interval, possibly Rhaetian.

Previous stratigraphic designation and stratigraphic association

Wanner (1956) noted a Weber locality on the track to Turiscai at about 9 km south-east of Remexio at what he called Fatu Rilau near Kaimuk. The position of this site is uncertain as names change through time. The locality included a reef limestone with corals and solenoporacean algae like the Upper Triassic fauna at Pualaca. It is probable that the Bandeira Formation is present at various localities in this area. This region (including Locality 6) was mapped as part of the “Ofiolitos e xistos cristalines (predominantemente paleozóicos)” by Grunau (1957) whereas Gageonnet and Lemoine (1958) included it in the Mesozoic of the “Autochone”. On Audley-Charles’s (1968) map, Locality 6 lies near the northern limit of an area mapped as Jurassic Wailuli Formation, and south of the Permian Maubisse Formation mapped along the “Ramelau Range”. Unpublished reconnaissance work by E. McCartain along the Daisoli River close to Locality 6, found outcrops of the Cribas Group (siliciclastic-volcaniclastic Permian facies).

Locality 7: Mt Lilu region

Rock types sampled

Samples of the Bandeira Formation were examined from four localities in a topographically high block close to Mt Dilu 4.5 km west of Manatuto town (Figs. 1, 4; Appendix 3). All samples are rudstone and have a grain assemblage (Appendix 4) like that in Units 1 and 5 at the formation’s type locality (Haig et al. 2025, locality 1). Micritic clasts, involutinid foraminifers, robertinid foraminifers (mainly duostominines), and recrystallized bivalve fragments are present in each sample. Other bioclasts of variable distribution are aggregate carbonate grains, solenoporacean algae, dasyclad algae, Microtubus encrustations, carbonate-cemented agglutinated/microgranular foraminifers and nodosariids.

Foraminifera

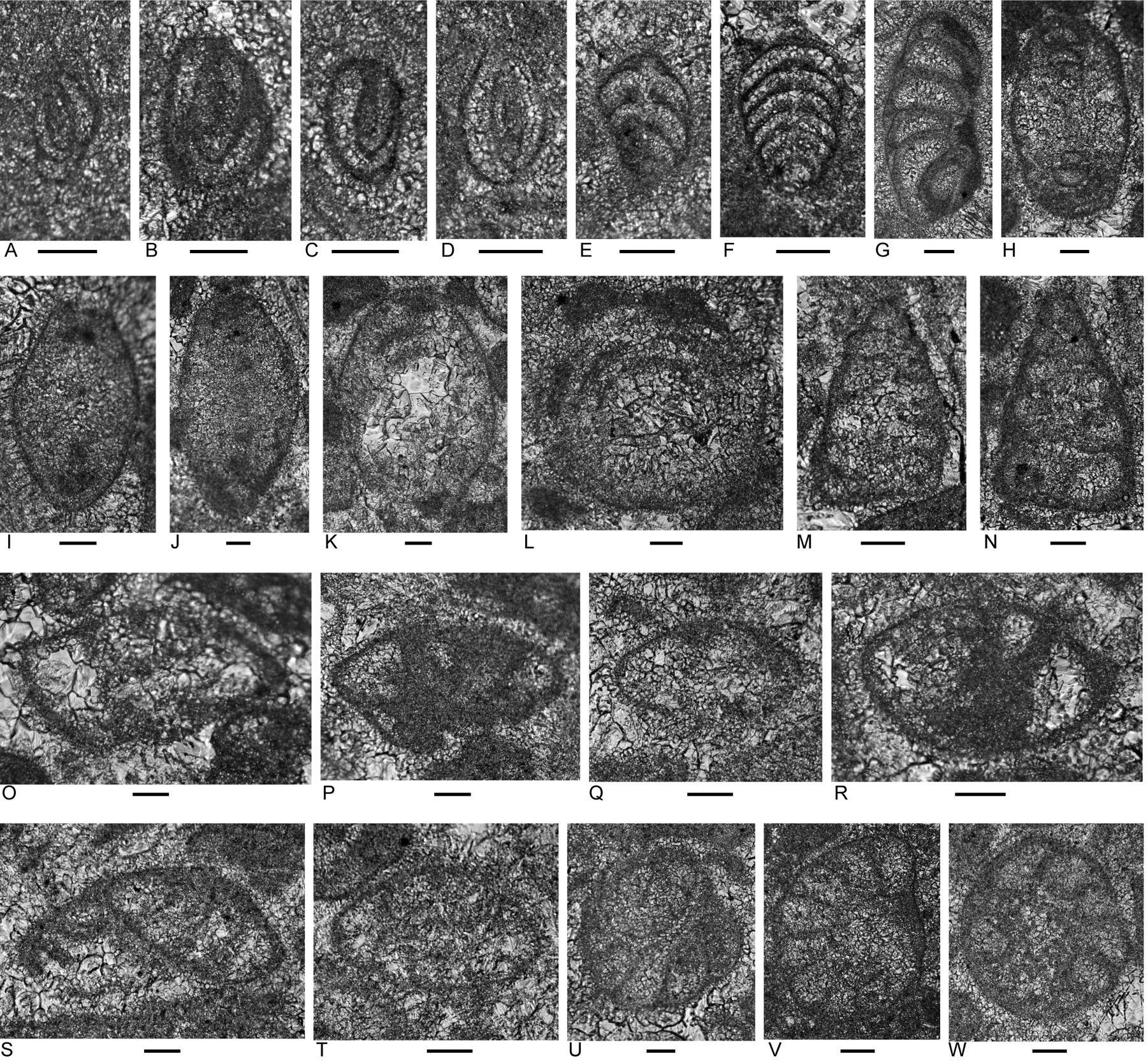

A low diversity foraminiferal assemblage of 10 species (Figs. 5, 6; Appendix 4) is present in the studied samples. Genera include the carbonate-cemented agglutinated/microgranular Duotaxis, Endoteba, Endotebanella, “Everticyclammina”, and possible Gandinella; involutinids Aulotortus and Parvalamella, and duostominines Duostomina and Cassianopapillaria.

Age

The foraminiferal assemblage is characteristic of the Triassic based on the general taxonomic composition and the ranges of species (Appendix 5). Based on the presence of Aulotortus communis (Fig. 5Q–X) the age is within the Norian to Rhaetian interval. The position of this species in the evolutionary succession of involutinids was established by Koehn-Zaninetti (1969, fig. 21) and Zaninetti (1976) although see a different version by Piller (1978) involving species synonymies and updated generic attributions. The species was originally described as Angulodiscus communis Kristan 1957, type species of Angulodiscus Kristan 1957 which we regard as falling within the broad spectrum of Aulotortus. Other foraminifers identified to species or species-group level provide broader age limits based on presently known stratigraphic ranges (Appendix 5): Endoteba obturata (ex. gr. morphotypes, Fig. 5F, H–K), Anisian–Norian; Endotebanella robusta (Fig. 5L), middle Anisian; Endotriadella wirzi (“aff.” morphotype, Fig. 5G), uppermost Olenekian–Carnian; “Everticyclammina” cf. simplex (Fig. 5N), Carnian. The presence of these species associated here with A. communis suggests that some aspects of their known stratigraphic ranges require revision.

Previous stratigraphic designation and stratigraphic association

A thrust block of Maubisse Formation surrounded by Wailuli Formation was mapped by Audley Charles (1968) in the Mt Lilu region, partly following the interpretations of Grunau (1957), who mapped the region as “Triásico (perto de Pualaca também Jurássico)” and Gageonnet and Lemoine (1958), who mapped limestone blocks as “Permien charrié (série de Maubisse, série de Sonnebait)”. Nakazawa and Bando (1968) produced a sketch map of the Mt Lilu area and found “Fatu limestones” dated as Triassic and possibly Permian, as well as “flysch-like” interbedded sandstone and shale of “Mesozoic (Triassic?)” age. The limestones included a reddish brown ammonoid-rich limestone and a grey-brown massive limestone dated as Early Triassic by ammonoids and conodonts; and a dark grey limestone, attributed to the Ladinian or lower Carnian, containing abundant Daonella bivalves and conodonts (Nakazawa and Bando 1968). The conodonts were also taxonomically catalogued by Nogami (1968). Grady and Berry (1977) mapped the limestone as Permian. More detailed mapping of the area by Berry et al. (1984, their fig. 2) established the “Lilu Beds” for “red and white limestone, shale with minor arkosic sandstone, and altered basalt and shale with minor limestone and graywacke”. They concluded that this unit belonged to the “upper Lower and Middle Triassic possibly ranging down to the Permian”. They also noted a white gastropod limestone and a thin-bedded white limestone. Surrounding their Lilu Beds they mapped a unit of shale with minor arkosic sandstone interbeds that they called the “Condar Beds”. Haig and McCartain (2007, their fig. 7b) demonstrated that a thin-bedded carbonate pelagite outcropping on the western part of the summit area on Mt Lilu belonged to the Turonian (Upper Cretaceous).

In more recent unpublished studies of this area, we have recognized the Permian Maubisse Group including Colaniella beds of Wuchiapingian (Late Permian) age. A structurally conformable contact has been identified between Triassic ammonoid-rich limestone that is stratigraphically condensed (probably as old as latest Griesbachian, lower Induan; designated the Lilu facies by McCartain et al. 2024) and the underlying Permian Maubisse Group. Shallow-water limestone of the Bandeira Formation has been found structurally above (and possibly progradational from) the Lower to Middle Triassic Lilu facies in this area. Surrounding the limestone outcrops is the Babulu Group (equivalent to the Condar Beds of Berry et al. 1984). These units collectively belong within the East Gondwana Interior Rift Association and the carbonate-pelagite on the summit of Mt Lilu described by Haig and McCartain (2007) belongs to the post-breakup Timor–Scott Plateau Association (see Appendix 2).

Locality 8: Pualaca region

Rock types sampled

Three rudstone samples of Bandeira Formation were studied from this area (Figs. 1, 7; Appendices 2, 3). They come from two slumped blocks of massive limestone in the Mota Mutin. Clasts, typical of limestones in the formation, include micritized fragments, porostromate calcimicrobes, solenoporacean algae, robertinid (duostominine) foraminifers, calcareous sponges, gastropods, and echinoid spines. Other grain types include oncoids, reworked shallow-marine limestone clasts, Microtubus encrustations, carbonate-cemented agglutinated and involutinid foraminifers, possible corals, encrusting bryozoans, impunctate and punctate brachiopods, recrystallized bivalve fragments and fragments with prismatic microstructure, indeterminant echinoderm debris, and ostracods.

Foraminifera

A low diversity foraminiferal assemblage, typical of the Triassic, has been recognized in the samples (Figs. 8, 9; Appendix 4) belonging to the following genera: carbonate-cemented agglutinated/microgranular Duotaxis (but for “Duotaxis nanus” considered uncertain by Falzoni et al. 2025), ?Endoteba, Endotebanella, “Everticyclammina”; involutinids Aulotortus; and duostominines, ?Cassianopapillaria, Diplotremina, and Duostomina.

Diplotremina altoconica (Fig. 9A–F; Appendix 4), which ranges from Carnian to Norian (Appendix 5), is present. The assemblage lacks species of Lamelliconus and Prorakusia as well as Parvalamella? praegaschei common in Carnian Unit 1 of the type Bandeira Formation (Haig et al. 2025). Although Aulotortus sinuosus (Fig. 8Z–ZB; Appendix 4) is present, the Norian–Rhaetian Aulotortus communis is absent distinguishing the observed Pualaca assemblages from those at localities 3, 4, 7, 9-2, 9-3, and 10 (Appendix 4) and from localities 3 and 4 of Haig et al. (2025). The age is probably early Norian or late Carnian.

Previous stratigraphic designation and stratigraphic association

The area of dismembered formations around Pualaca (Locality 8, Figs. 1, 7) has not been detailed in published reliable maps. Charlton et al. (2009) summarized previous work in the region. Triassic rocks in this area were found initially by Hirschi (1907) who observed thin-bedded dark limestones and interbedded mudstones that contained halobiid bivalves, which are now placed into basinal Triassic facies (either Babulu or Aitutu formations; see Appendix 2). He also described outcrops of light-grey thick-bedded to massive crystalline limestone that in places contain corals and suggested a possible Triassic or young Paleozoic age. The Jurassic strata that Hirschi (1907) recognized are now placed within the Wailuli Formation; and the young Paleozoic reddish-brown limestone with the trilobite Phillipsia is placed within the Permian Maubisse Group.

Wanner (1956) reviewed palaeontological work done on samples collected by Friedrich Weber during 1910–1911 around Pualaca, particularly the work on corals and algae by Vinassa de Regny (1915) and on molluscs and brachiopods by Krumbeck (1921). He noted differences in age determinations by these authors. The two main localities with Upper Triassic coralline limestones were Fatu Laculequi (A on Fig. 7) and Fatu Naruc (B on Fig. 7). On the bases of brachiopods, Krumbeck (1921) suggested that the Fatu Laculequi limestone belonged probably to the upper Carnian, whereas Vinassa de Regny (1915) found that the corals in this fatu and in Fatu Naruc were known, at generic level, from the Zlambach Beds in Austria, now considered Rhaetian. Yamagiwa (1963) also described the corals from Fatu Laculequi. As well as other localities of the Fatu Limestone facies, Wanner (1956) noted in this area many Weber localities of basinal mud facies with Ladinian to Norian halobiid bivalve faunas.

Grunau (1957) mapped a large area in the Pualaca region as “Complexo de Corbertura” with “Ofiolitos e xistos cristalines” and “Pérmico” and “Calcários de Fato de idade indeterminada em parte triásicos”. According to his map, east of Pualaca was “Complexo Autoctono” with “Triásico (perto de Pualaca também Jurássico)”. He noted that Mt Bissori was a diabase and Permian in age because of its close association with Fenestella limestone. He also suggested that Mt Calaun and Mt Fehuc (see Fig. 7) were unfossiliferous, in terms of macrofossils.

Gageonnet and Lemoine (1958) mapped “Calcaires Fatu (Complexe Charrie)” as a narrow ovoid area including ?Bissori, Calaun and Fehuc mountains (Fig. 7) west of Pualaca and trending south; with a small area of “Roches métamorphiques et éruptives (Complexe Charrié)” at the southern margin, near Soibada. This was designated by Audley-Charles (1968) as the Lower Miocene Cablac Limestone with the mainly volcanic Barique Formation on the southern margin, and the area surrounding it and to the east of Pualaca represented by the “Upper Triassic–Middle Jurassic” Wailuli Formation. Audley-Charles (1968) did not differentiate the Upper Triassic coralline limestones that earlier workers had described. Charlton et al. (2009) referred to these as the “Pualaca facies”.

Field observations and sampling by us (including McCartain, 2014*, 2024; Haig et al. 2021b; Barros et al., 2025) confirms that two main tectonostratigraphic associations are present in the region (Fig. 7) although the boundary between these can only be tentatively positioned before detailed mapping takes place. In the EGIRA area (Fig. 7), Mt Lafulolau, Mt Bissori and associated limestone (see Nogami, 1963; Nakazawa and Bando, 1968) and limestone in an area immediately south of Mt Aubean are Permian (Maubisse Group). Our limited sampling at the side of Mt Aubean suggests that the limestones here are of Triassic shallow-marine facies, but foraminifers have not been observed. Basinal mud facies of the Middle and Late Triassic (Babulu and Aitutu formations) are present on the western and eastern slopes of Mt. Nono Lulik and around Pualaca and on the lower western-facing slopes of the Mota Mutin valley (see also Nogami, 1968; Nakazawa and Bando, 1968). The Upper Triassic Bandeira Formation is present in small outcrops on the eastern side of Nono Lulik to the Mutin River. East of the Manatuto–Natarbora Road, Lower Jurassic shales of the Wailuli Group outcrop. The Bandeira Formation in the Pualaca area is associated with the Permian shallow-water limestones, and the Triassic and the Lower Jurassic basinal mud deposits in EGIRA (see Appendix 2) as Wanner (1956) suspected.

In the Mota Samora that flows through a deep gorge between the Calaun and Fehuc mountains, large boulders of oncolitic limestone are present containing a Lower Jurassic foraminiferal assemblage including the complex carbonate-cemented agglutinated foraminifer Lituosepta (Haig et al. 2021b) A sample of oolitic limestone on the crest of Mt Fehuc at its southern side includes a foraminiferal assemblage with abundant Siphovalvulina, ?Nautiloculina, and Textulariopsis, and may be upper Lower Jurassic or Middle Jurassic. These limestone facies belong within the Perdido Group and are associated here with mafic volcanic and metamorphic rocks as indicated by Hirschi (1907), Gageonnet and Lemoine (1958) and Audley-Charles (1968). This is typical of OTA. We are uncertain about the age or tectonostratigraphic affinity of the Mt Calaun rocks (Fig. 7).

Locality 9: Iralalaru Boreholes, Paitchau Range

Two continuously cored shallow boreholes, closely spaced, in the Paitchau Range (Fig.10) have been examined in this study. These were drilled in 2006 by the then Ministry of Natural Resources, Minerals and Energy Policy with assistance and funding from the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (2006*). The aim was to assess rock quality and possible karstic features in the crystalline limestone present in the range (Geotechnik Pty Ltd. 2006*).

No lithological log or completion report on the boreholes have been available for the present study and may not have been made. We have no information as to the younging direction of the cored section (i.e. whether the strata have been overturned). The core (Fig. 10C, D), examined in 2016 when it was housed at the Electricity Commission building in Dili, showed large gaps with broken core pieces probably due to numerous cavities within the rock. The two boreholes, drilled in proximity, provide intermittent coverage down to about 170 m below surface. Because of the steep dip of strata, the stratigraphic thickness traversed was much less. In the drilling log, prepared by Geotechnik Pty Ltd. (2006*), the boreholes were divided into three units, of which only the upper two were cored (Fig. 10A).

For this study, the taking of core material for study was prohibited. Cutting the core transversely at regular intervals and making acetate peels from the slabbed surfaces was permitted. Eighty-seven peels were prepared on site (Appendix 3). The distributions of grain types and foraminiferal species are charted in Appendix 4, and the representative foraminifers are illustrated in Figs. 11–13. In the discussion below, the cored sections are referred to as (1) the upper massive limestone unit (to about 63 m depth below surface), and (2) the middle unit (from about 62 m to 167 m below surface).

Upper massive limestone unit

Rock types sampled

In the upper massive limestone (down to about 63 m in the boreholes; Fig. 10A), rudstone dominates with grainstone and wackestone represented in very few samples (Appendices 2, 3). Almost all samples contain abundant to common micritic clasts ranging from peloid to nodule size. Among the biogenic components, the most persistent grain types (present in at least half of the samples and listed here in a decreasing order of persistence) are porostromate calcimicrobes, involutinid foraminifers, recrystallized bivalve fragments, robertinid foraminifers (mainly duostominines), gastropods, carbonate-cemented agglutinated or microgranular foraminifers and ostracods. Other types present in fewer samples are reworked shallow-marine limestone clasts, solenoporacean algae, dasycladacean algae, Microtubus encrustations, Tubiphytes, porcelaneous foraminifers, very rare nodosariid, vaginulinid and polymorphinid foraminifers, calcareous sponges, very rare, isolated sponge spicules, very rare possible bryozoans, impunctate brachiopods, and echinoderm debris including echinoid spines. This grain assemblage is typical of the Bandeira Formation elsewhere and with the distinctive involutinid and duostominine foraminifers is typically Triassic.

Foraminifera

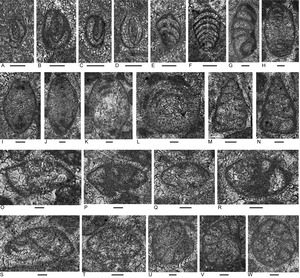

Foraminifers from the upper massive limestone include a diverse assemblage although sporadic in distribution (Appendix 4). Genera include the carbonate-cemented agglutinated/microgranular Duotaxis, Endoteba, Endotriadella, “Everticyclammina”, Gandinella, Hoyenella, Rectoglomospira, and “Tolypammina”; involutinids ?Aulosina, Aulotortus, Parvalamella, and Triasina; the polymorphinid Eoguttulina, and duostominines Diplotremina and Duostomina. This assemblage is typically Triassic.

Age

Among the foraminifers (Appendix 4) are very rare Triasina hanktkeni (sample 107, 58.5 m in #2 borehole; Fig. 12ZF), possible intermediate forms between Aulosina and Triasina (Fig. 12ZC, ZD), Aulotortus communis, morphotypes close to Aulotortus sinuosus but with strengthenings in final whorls, Aulotortus tumidus, and Diplotremina subangulata. These collectively suggest a possible Rhaetian age, or at least no older than Sevatian (late Norian) based on ranges given in Appendix 5.

Middle limestone unit

Rock types sampled

The middle unit recognized in the boreholes (Fig. 10A), from about 62 m to 167 m, consists of minor limestone intervals, that were cored, separated by friable sections. Micritic clasts and porostromate algae are present in all samples. Other persistent grain types (listed in order of decreasing persistence; Appendix 4) are involutinid foraminifers, recrystallized bivalves, gastropods, dasycladacean algae, carbonate-cemented/microgranular agglutinated foraminifers, and robertinid foraminifers. Other components that are present in fewer limestone beds are solenoporacean algae, Microtubus encrustations, Tubiphytes, procelaneous foraminifers, nodosariid, vaginulinid and polymorphinid foraminifers, calcareous sponges (in only one sample), bryozoans, impunctate brachiopods, bivalve with prismatic microstructure (in one sample), indeterminant echinoderm debris and echinoid spines, crinoid columnal plates (in one sample) and ostracods.

Foraminifera

A moderately diverse assemblage of foraminifers is present (Appendix 4). Genera include: carbonate-cemented agglutinated/microgranular Duotaxis, Endoteba, Endotriada, “Everticyclammina”, Gandinella, Hoyenella; involutinids ?Aulosina, Aulotortus, Parvalamella, Triasina; and duostominines Diplotremina and Duostomina. The fauna is like that in the upper limestone unit.

Age

Triasina hantkeni is present in sample 91 from the lower part of the middle limestone unit (Appendix 4; Fig. 10a). This species indicates a probable Rhaetian age also is present in the upper limestone unit. It occurs with morphotypes that seem transitional between Aulosina and Triasina. Among the stratigraphically important foraminifers in the middle limestone unit, Aulotortus sinuosus (Fig. 12ZE) and Parvalamella friedli (Fig. 12W–Y) are the most persistent species but have a broad Middle to Late Triassic range. Much more sporadic are possible Aulosina oberhauseri, Aulotortus tumidus, Diplotremina subangulata (Fig. 13Q). The overall assemblage suggests a Norian–lower Rhaetian correlation (see Appendix 4 for ranges and references).

Previous stratigraphic designation and stratigraphic association

In a report written before the boreholes were drilled, the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE 2006*) noted that a light-grey massive crystalline limestone was well exposed on the steep southern cliff of the Paitchau Range (Fig. 10B). They dated this as Permian–Carboniferous by foraminifers including “Staffela Ozanwa” (NVE 2006, p. 11 of their Chapter 5) perhaps misidentified for the Late Triassic coiled duostominines that are abundant in some core samples (Appendix 4, Fig. 13). The limestone is in contact with a unit of alternating shale, siltstone, claystone and fine-grained calcareous sandstone, with interbedded limestone of supposed Permian age in its lower part. The crystalline limestone was designated the “Paitchau Limestone” and the dominantly shale unit was designated the “Cribas shale”.

Grunau (1953, 1957) mapped the Paitchau Range as “Fatukalke” of indefinite age, but partly Triassic surrounded by Triassic strata, and noted that the limestone contains only unclassifiable remains of gastropods and corals. Gageonnet and Lemoine (1958) included the Range in “Calcaires Fatu” of the “Complexe Charrié” (Overthrusted Complex) and noted that the massive limestones were apparently the same as those of the Tutuala area of Triassic age (although not dated in the Paitchau Range). Surrounding Paitchau Range they found “Mésozoique” of the “Autochtone” (Série de Kekneno - autochtone)". Similarly, Leme (1963) mapped the Paitchau Range as part of the limestone massifs of Tutuala (of Late Triassic age) surrounded by shale-sandstone facies of the “Triassic-Jurassic complex”. Audley-Charles (1968) included it in his Aitutu Formation, defined by radiolarian calcilutites and attributed the formation to the Upper Triassic. Charlton et al. (2009) correlated the limestone with the Pualaca facies (Upper Triassic) of locality 8. Benincasa (2015*) placed the Bandeira Formation at the core of the range complex surrounded by Aitutu Formation and, following previous authors, with Cribas Formation on the southern flanks of the Range. The Bandeira Formation in Paitchau Range is contiguous with other formations of EGIRA.

Locality 10: Tutuala area

Locality 10 of the Bandeira Formation is a hill on northern side of Tutuala town near the Pousada (Fig. 10).

Rock types

Twenty-two samples (Appendix 3) were examined from Locality 10. Peloidal-skeletal grainstone and packstone (difficult to distinguish because of extensive recrystallization of matrix) are the dominant rock types. One sample of ooid grainstone was examined. In this sample set, no nodular calcimicrobes or solenoporacean algae were observed. The most persistent clast types (listed in order of decreasing persistence; Appendix 4) are impunctate brachiopod fragments, punctate brachiopod fragments, carbonate-cemented agglutinated/microgranular foraminifers, indeterminant echinoderm debris, ostracods, recrystallized bivalve clasts, gastropods, nodosariid foraminifers, echinoid spines, and minor Microtubus encrustations, porcelaneous, involutinid and robertinid foraminifers, calcareous sponges, coral debris, bryozoans, bivalve fragments with prismatic microstructure, and crinoid columnals with pentagonal and circular cross-sections. This grain assemblage is typical of the Bandeira Formation and of the Triassic.

Foraminifera

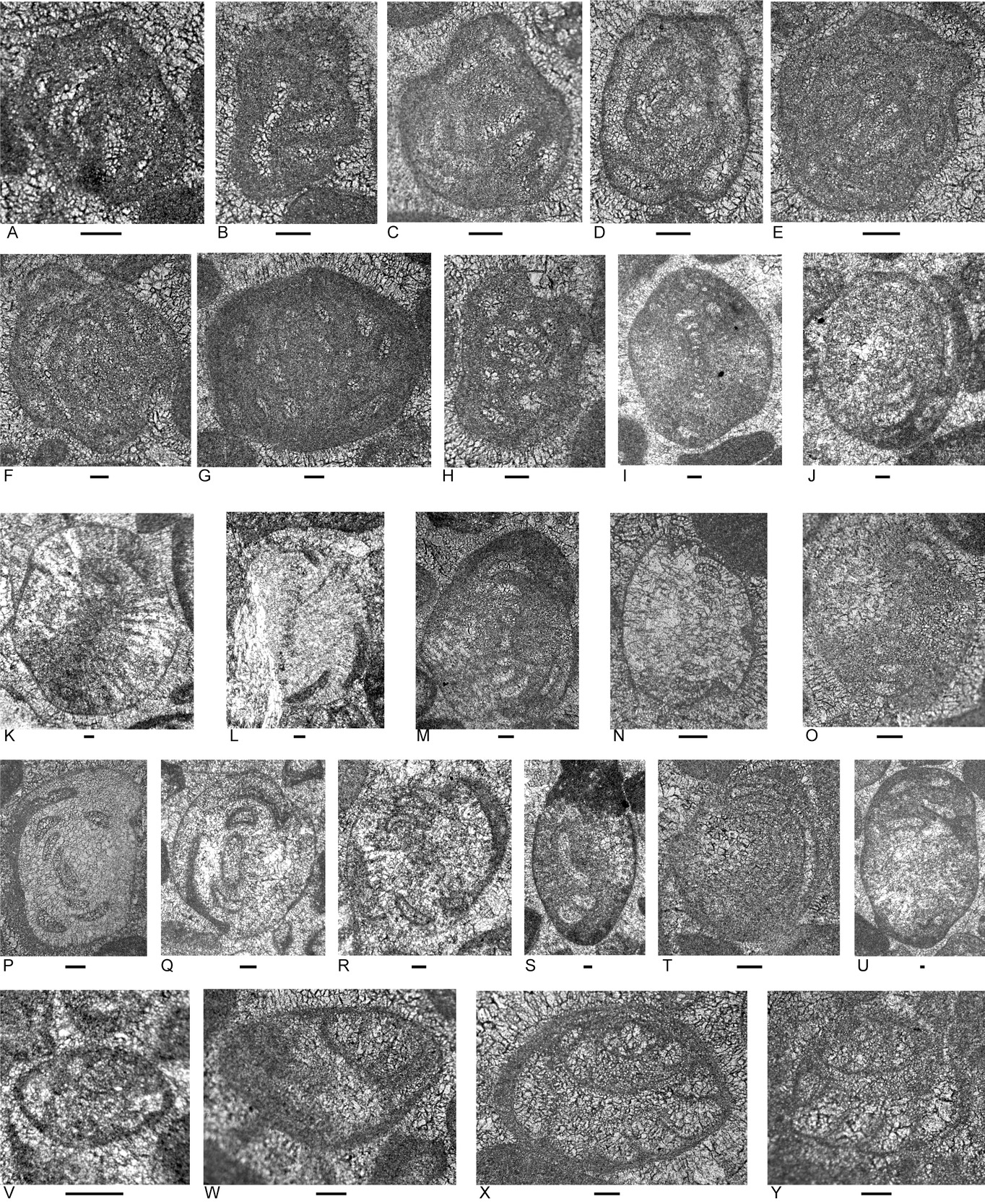

Foraminifers (Figs. 14, 15) are sporadic and rare among the samples. Genera include: carbonate-cemented agglutinated/microgranular ?Duotaxis, Endoteba, Endotebanella, ?Gandinella, Hoyenella, ?Piallina, “Tolypammina”; nodosarians Astacolus and Cryptoseptida; involutinids Aulosina, Aulotortus; and duostominines Cassianopapillaria, Diplotremina and Duostomina.

Age

The foraminiferal assemblage includes Aulosina obserhauseri (Fig. 15K, L), Aulotortus communis (Fig. 15H), Diplotremina altoconica (Fig. 15M, N), possible Diplotremina subangulata and indeterminant Cassianopapillariinae that collectively suggest a Norian correlation (see Appendix 5 for ranges and references).

Previous stratigraphic designation and stratigraphic association

Locality 10 is one of several limestone massifs around Tutuala (Wanner 1956; Leme 1963, 1968). From this area, Wanner (1956) noted that “upper Norian” massive coralline limestone is associated with “Carnian” radiolarian-rich limestone. Leme (1963, 1968) noted that the massive grey to light yellow limestone included intraformational conglomerates that contain a Triassic ammonoid, nautiloid and brachiopod assemblage, and that the limestone outcrop contains corals. Leme (1963, 1968) suggested that the coralline limestone at Tutuala and that from Paitchau Range (Fig.10) formed a “reef belt” located at the base of the Triassic succession. Audley-Charles (1968) described highly fossiliferous basal conglomerates of the Aitutu Formation around Tutuala, with an ammonoid assemblage suggesting a Carnian age. Charlton et al. (2009) placed the conglomerates in the Pualaca facies. The Locality 10 limestone at Tutuala belongs within EGIRA, which is consistent with the findings of Wanner (1956, Leme (1963, 1968) and Audley-Charles (1968).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

As demonstrated by Haig et al. (2021a; 2025) and Barros et al. (2022, 2025) the Triassic carbonate deposits of Timor-Leste contain distinctive suites of foraminifers that include age-diagnostic species. The shallow-water carbonate-platform facies, defining the Bandeira Formation, has a known stratigraphic range from within the Carnian to within the Rhaetian based on foraminiferal assemblages recorded from nine of the localities described in this paper in eastern Timor-Leste and by Haig et al. (2025) in western Timor-Leste (Fig. 16). Pre-Carnian occurrences of the Bandeira Formation are likely to be found because the cephalopod-rich “Lilu facies” (a submerged platform facies closely associated with the Bandeira Formation in the Upper Triassic, Barros et al. 2022) is known from the earliest Triassic (Berry et al. 1984; McCartain et al. 2024).

At all studied localities, the Bandeira Formation crops out next to exposures of the Babulu and Aitutu formations of the Triassic (middle Anisan to lowermost Rhaetian; McCartain et al. 2024). These units represent basinal mud facies that in some areas contain debris slides with clasts derived from the Bandeira Formation (e.g. Haig et al. 2007). In many of the studied areas, outcrops of the Permian Cribas Group (see Appendix 2) and the Rhaetian to Lower Jurassic Wailuli Formation (Appendix 2) are present close to the Bandeira Formation. It is noteworthy that no debris slides with Bandeira Formation clasts have been found in the Wailuli Formation. This is consistent with the Bandeira carbonate platform not persisting to young parts of the Rhaetian and not extending across the Triassic–Jurassic boundary. Despite the complex deformation, the assembly of stratigraphic units around outcrops of the Bandeira Formation indicates tectonostratigraphic affinity with the East Gondwana Interior Rift Association and is consistent with coeval facies farther south in relatively undeformed basins along the present-day north-western Australian margin. No units equivalent in age to the Bandeira Formation, and no debris slide deposits derived from it have been located within the Overthrust Terranes Association (Nano et al. 2023; Haig et al. 2024).

This contribution to understanding of the Bandeira Formation as well as that by Haig et al. (2025) has set out the distinctive microfacies and foraminifers that allow easy recognition of the formation (particularly in the field with use of a cement-cutting saw and basic inexpensive acetate-peel making equipment as explained in Haig et al. (2021a, 2025). In the past the formation has been confused with other units ranging from Carboniferous–Permian to Miocene, resulting in misleading and naïve tectonostratigraphic interpretations. The challenge now is to more precisely reconstruct the Late Triassic carbonate platform by more detailed facies analyses and more precise correlations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the people and various institutions in Timor-Leste (UNTL, SERN, IPG, IGTL, ANPM, TIMORGAP) for their generosity and hospitality that continues to facilitate our field studies initiated in 2003. We are grateful to our many colleagues in Timor-Leste, Australia, and elsewhere who have contributed to our knowledge of the complex and fascinating geology in this region. We thank Timor Resources for providing logistic support for some of our 2018 field work. Haig thanks the University of Western Australia, and in particular the Oceans Institute that in recent years has provided a stimulating and pleasant base for continuing these studies in retirement. Over the last 15 years this has been a self-funded project. We would like to thank Luka Gale and an anonymous reviewer for their helpful comments on the original 2021 version of the manuscript published in Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, and to Barry Taylor and Arthur Mory for commenting on this and the Haig et al. (2025) versions of the originally unpublished supplementary files.

_showing_s.tif)

)_showin.tif)

)_showing_the_positio.tif)

.tif)

).tif)

)._b.tif)

)._b.tif)

_showing_s.tif)

)_showin.tif)

)_showing_the_positio.tif)

.tif)

).tif)

)._b.tif)

)._b.tif)